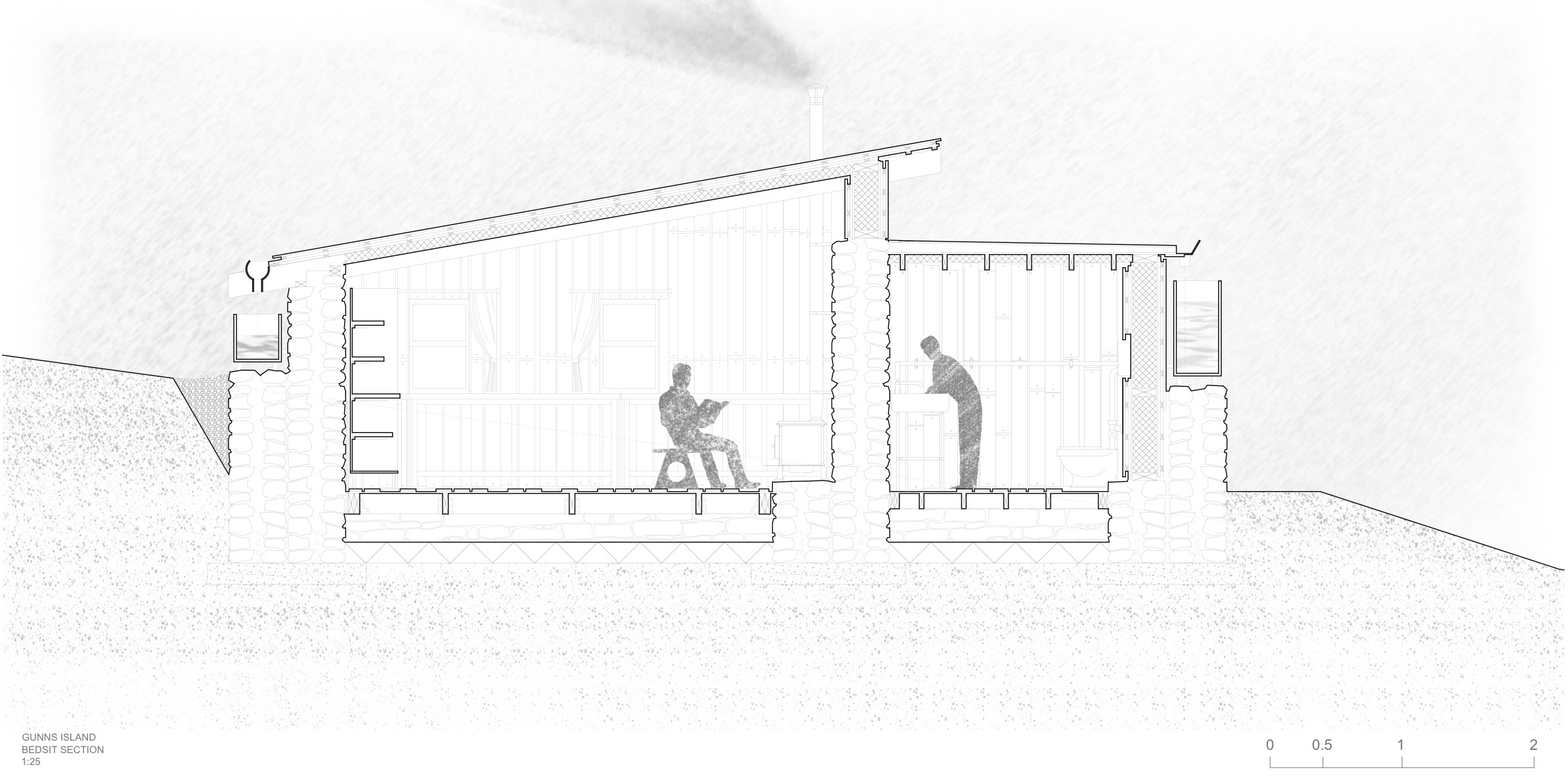

This thesis aimed to explore the use of narrative design in the region of Lecale in Co. Down. Off the coast of Ballyhornan lies a tidal piece of land, Guns Island, draped in history and mythology. I used the hermit of Guns Island as a design tool to explore the importance of narrative within architecture.

Using a story to communicate ideas presents a clear and rational method of individual experiences and how we understand our conditions. Framing design proposals as a narrative shows a perspective to clients and the public, as we all understand the importance of storytelling and its value. People may not understand design concepts, but they do understand stories. Rebecca Solnit professed that “Stories are compasses and architecture, we navigate by them, we build our sanctuaries and our prisons out of them, and to be without a story is to be lost in the vastness of a world”. Storytelling adds meaning where design cannot. Though drawings and a finished design show what can be done in the real world, narrative design shows process and progress, giving design structure.

The hermit’s story on Guns Island helped solidify the potential for new users to inhabit the island. The hermit’s philosophy is integral to his character. The folklore of his life on the island gives the island character that needs to be respected.

Through a narrative design lens, we can create suitable accommodation on an island, respecting the history and philosophy of the hermit’s way of living. The narrative helps influence the design’s form, technology and spatial qualities.

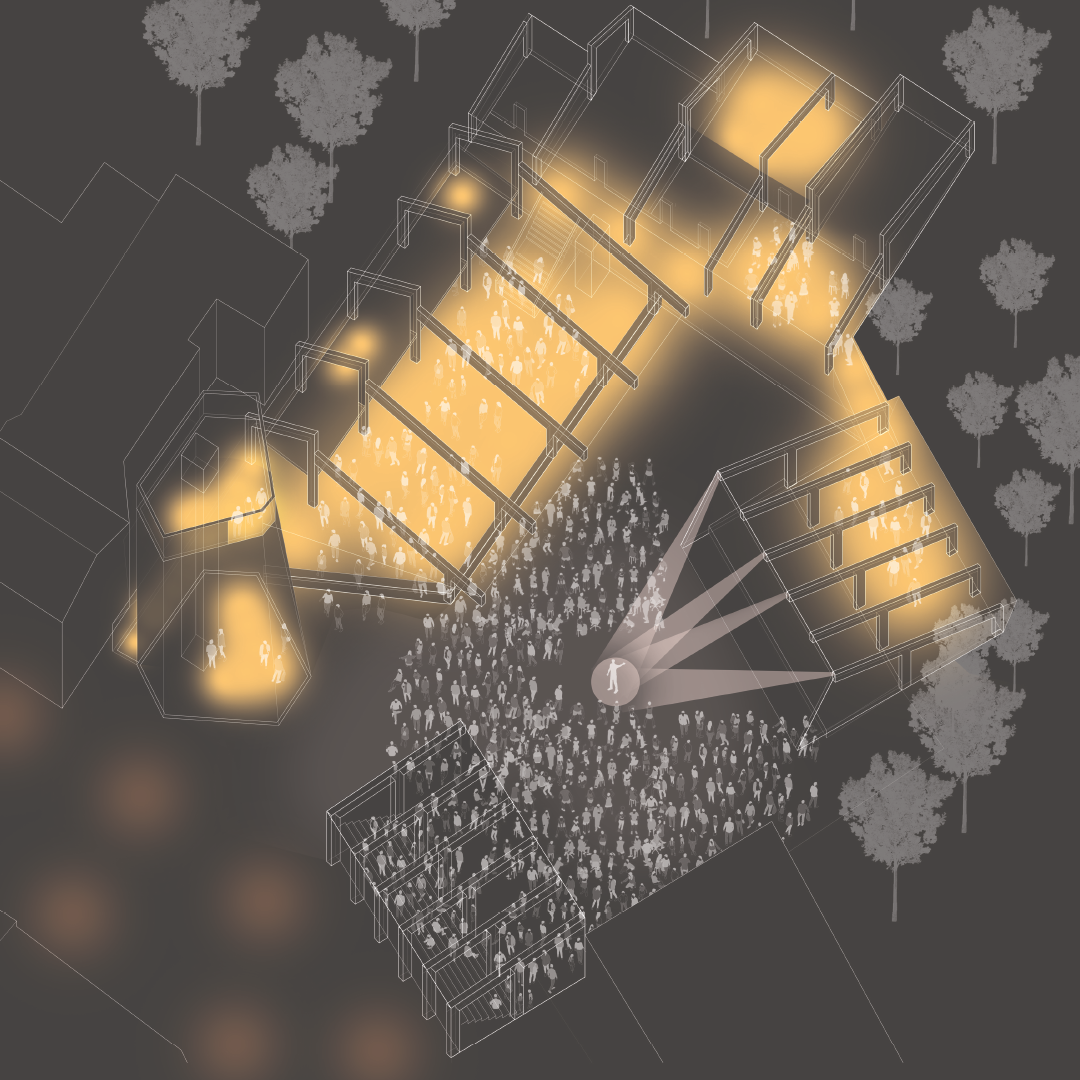

The overall ambition of this adaptive-reuse and regeneration project was to inject new life through careful architectural intervention into the currently overlooked, and underutilised area of the Stranmillis campus around the Henry Garrett building. This is accomplished through the partial adaptive reuse of the Henry Garrett building, and the intervention of a loggia to activate the central, overlooked meadow space as an informal courtyard. The architectural challenges of this site included, the poor utilisation of the existing natural environment, partly due to the imposing road network throughout the campus that limits pedestrian movement around it. The relative lack of formal public areas for socialising and working, which include the stunning woodland and grass areas around the campus which create opportunities for informal social spaces, however they are not utilised due to the poor spatial layout of the campus, with disconnected buildings and pedestrian paths intercepted by roads. And finally, the fact that the Henry Garrett building itself, a Grade B+ listed red brick former multi purpose educational building, constructed in the late 1940’s, is laying derelict, in a state of disrepair.

The renovation of this building could be a key intervention into unlocking the overlooked potential of the campus, as well as being crucial to preserving, and continuing to utilise the unique built heritage of Belfast. The success of the proposed intervention should re-animate this area into a socially cohesive, engaged space that will be utilised by future generations. The interventions are designed to outlast the Henry Garrett building, therefore as the existing fabric of the building further disintegrates over time, the intervention will remain, redefining the spatial alignment of the space to be shaped by future generations.

“Every building must create coherent and well-shaped public space next to it”(Christopher Alexander, in “A New Theory of Urban Design” 1987)