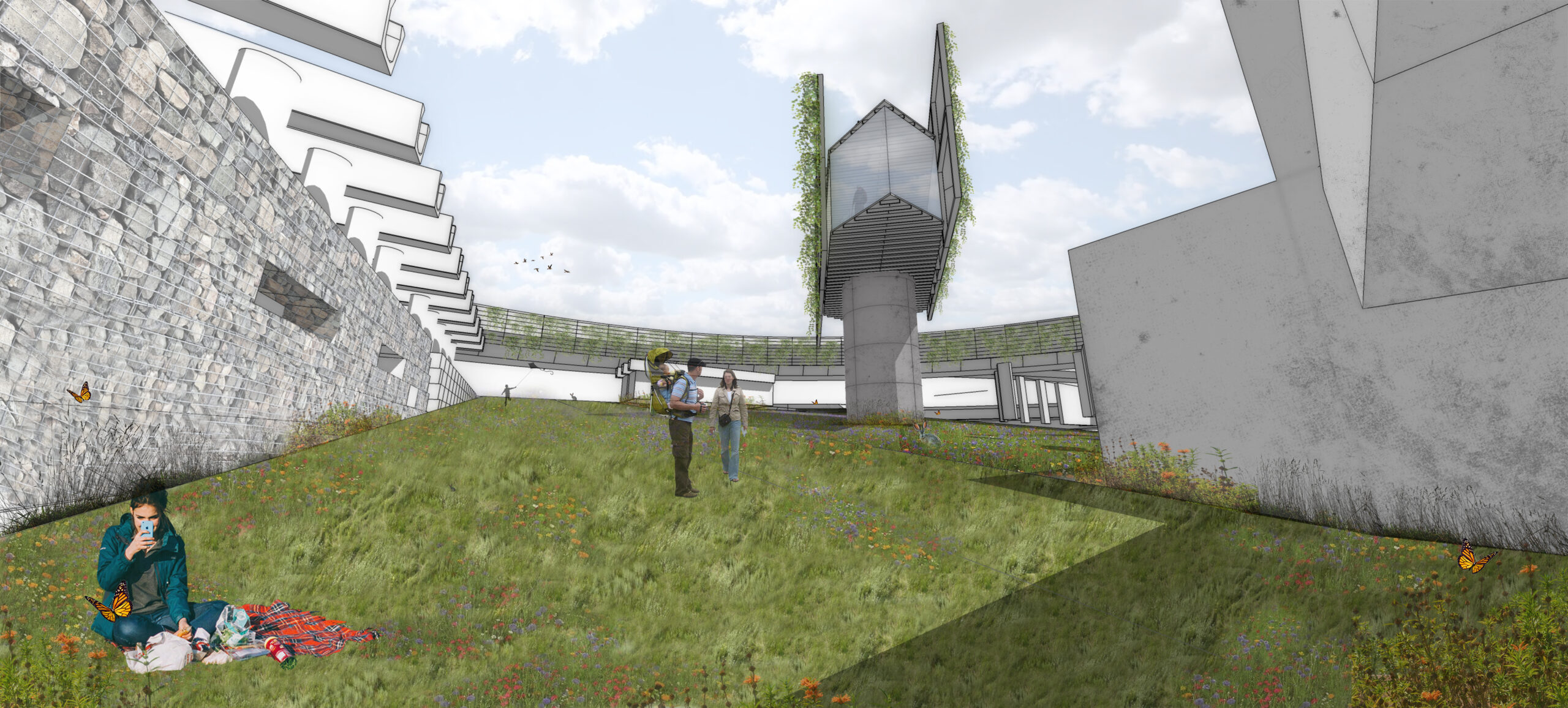

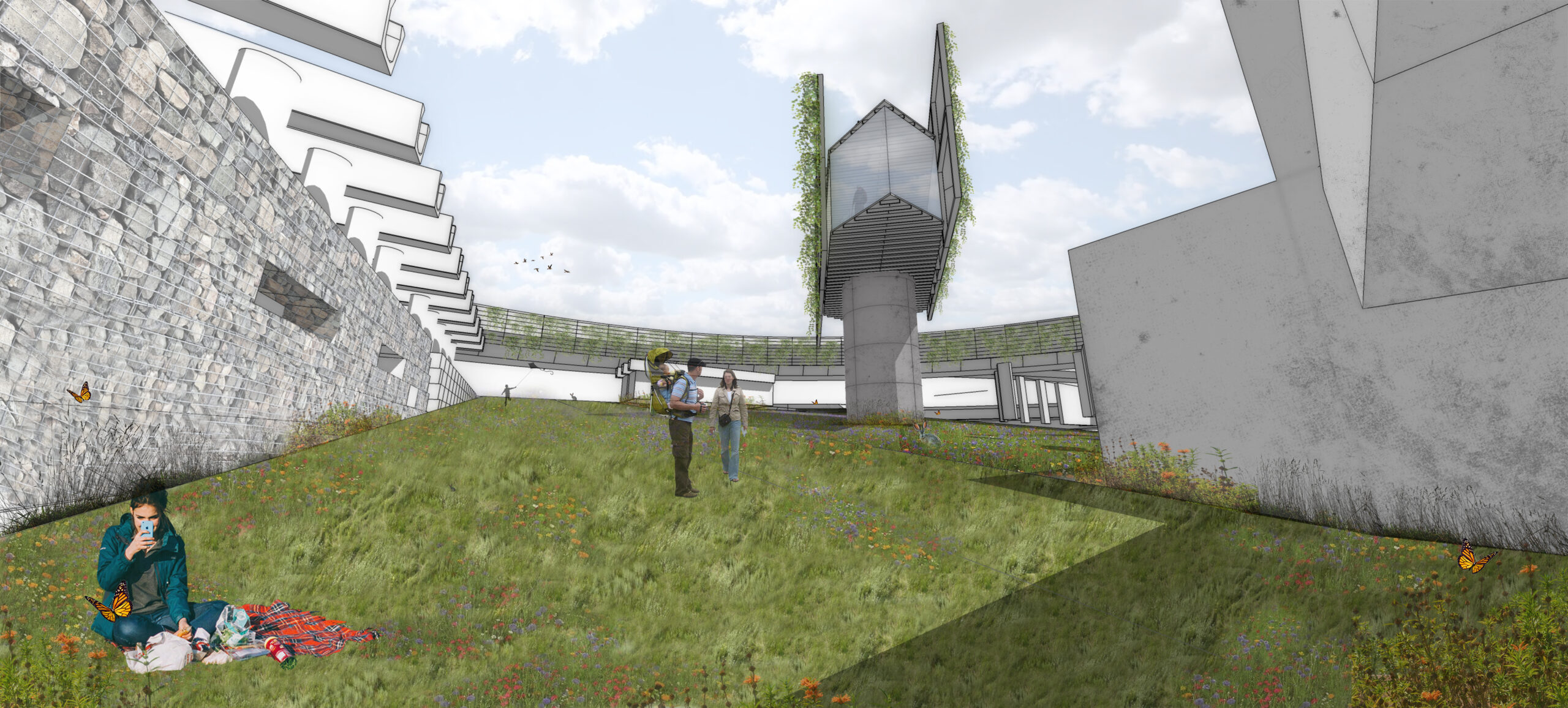

My research thesis focused on the issue of non-place, in particular in and around infrastructural networks. In scouring the countryside for places that had been diluted or destroyed by infrastructural expansion, I discovered the Corbally canal, a truncated spur of the Grand Canal intended to run from Naas to Hacketstown, until financing ran out 5 miles south of Naas, resulting in a harbour and harbour master’s house in a middle of a field in Kildare and a useless stretch of canal, all separated from the roaring M7 motorway by a thin sliver of land. The canal had been culverted in the 1940s and wasn’t navigable. As a result it has become a sealed and undisturbed ecosystem, home to rare plant and insect life due to its unique condition, in effect a linear nature reserve. Moved by the strangeness of this anomaly, the due diligence rabbit-hole lead to the discovery that planning applications in the vicinity were being rejected due to the presence of a JPZ (Junction Protection Zone) This area was earmarked for a connecting intersection for the Leinster Orbital Route, a new gyratory outside the M50 connecting Naas to Drogheda. Another layer of speed and movement was looming, to further dilute the character of strange abandoned 18th century harbour and the isolated spur of canal. The project aims to intervene here, to engage with the new spaghetti junction and offer an off-ramp to the linear nature reserve below and additionally a place to study its unique condition. It presents two very different facades to very different speed of passers-by, some at 120km/h, others at 5km/h.

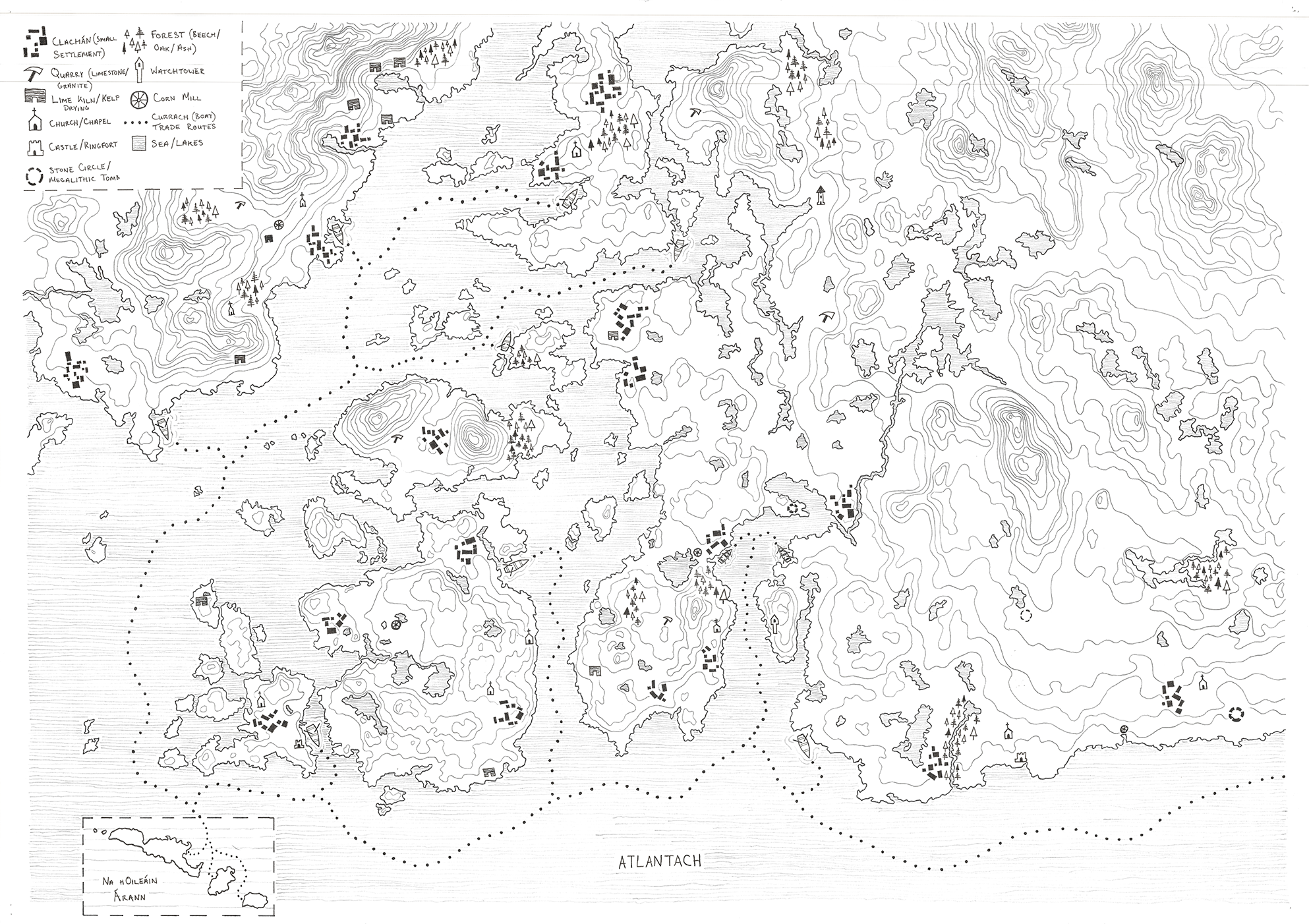

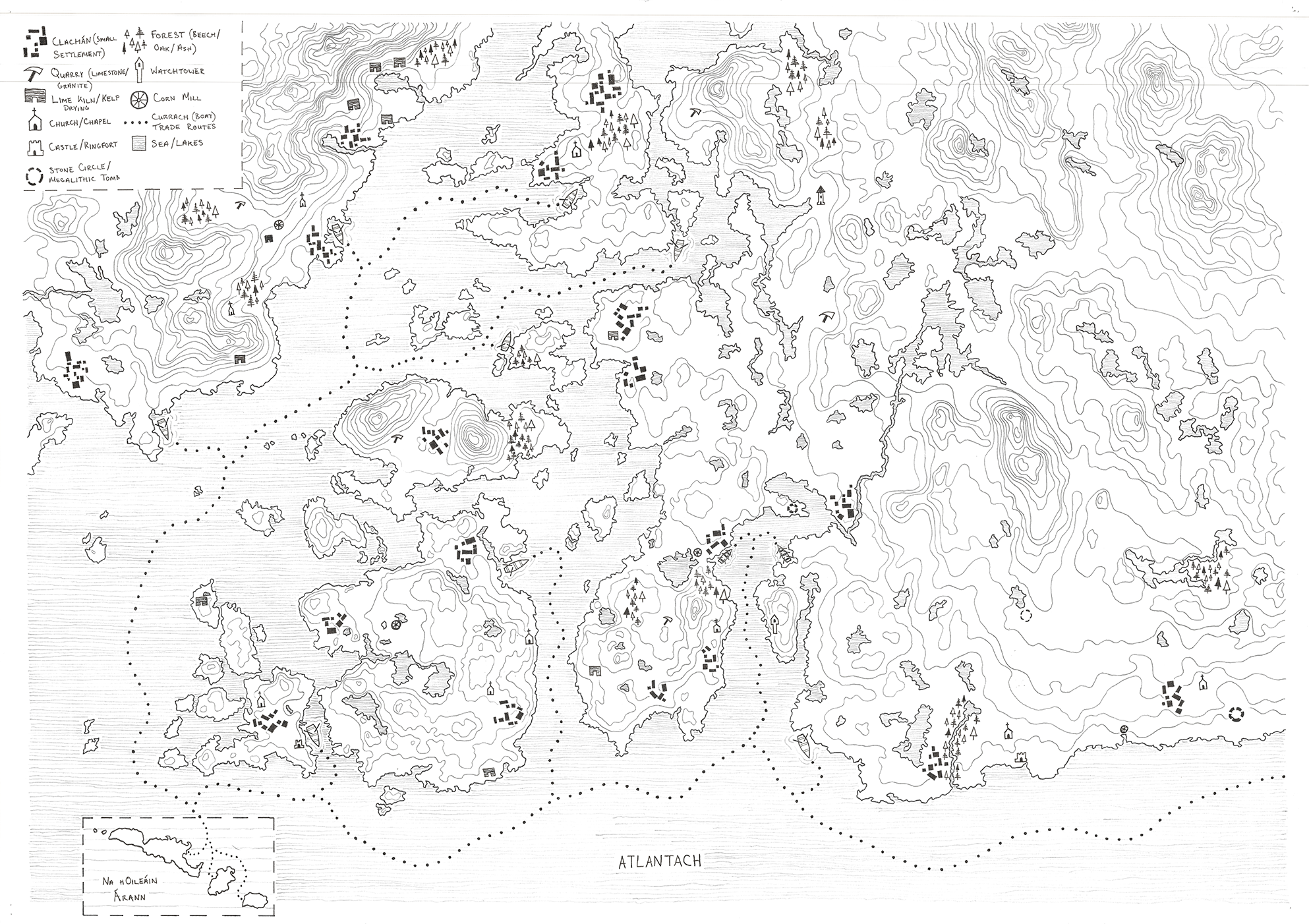

This thesis considers our relationship with land. It is an architectural proposal that stems from a collection of historical, theoretical, and analytical studies of our past inhabitation in the West of Ireland. It celebrates a past connection to place, material, and one another. It outlines the resilient nature of the early Western settlers in terms of placemaking, despite the aggressions of the wild winter swells, sterile soils, and sharp south-westerly winds. Ultimately, it is a study of an environmentally-sensitive architecture, unaccompanied by architects, in the hope of alleviating the customary destruction of cultural landscapes and stimulating an argument for how we live, where we live, and

what we build with.

The chosen site is in the rural village of an Cheathrú Rua ‘Carraroe’, county Galway. It lies in the heart of a peninsula in a Gaeltacht (Irish-speaking) region of Connemara. As a result of the climate crisis and rising sea levels, the peninsula will become an island and the village of Carraroe will become a coastal town by 2090.

The project hopes to propose a new prototype for building in these vulnerable landscapes. This prototype aims to reactivate the existing windswept nodes of human inhabitation speckled along the west coast of Ireland, with a refreshed sensitvity to cultural landscapes. The design endeavours to allow spaces for biodiversity, island culture, and community to flourish while negotiating the subsequent changing terrain over time, as the village welcomes a new tide.

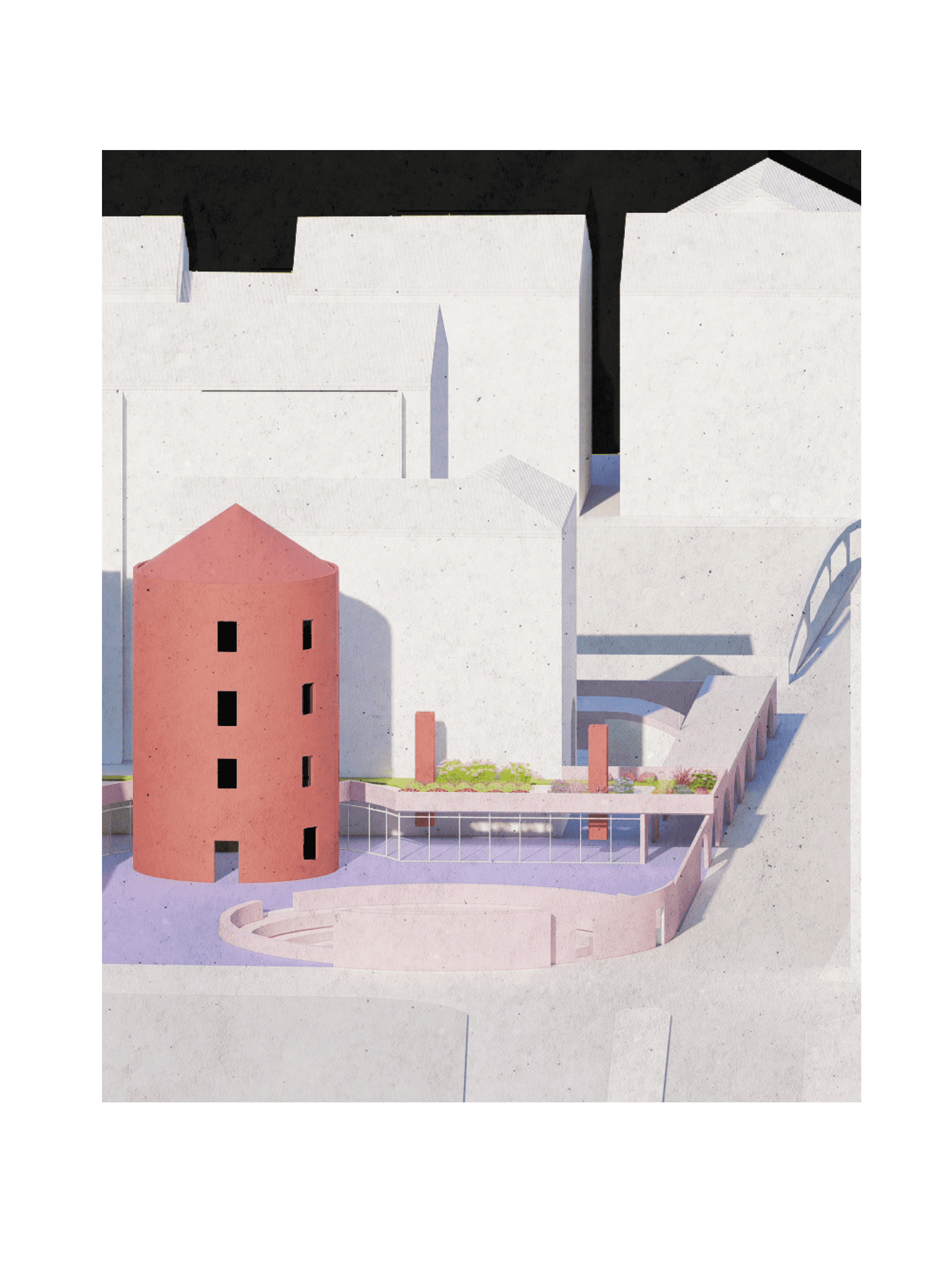

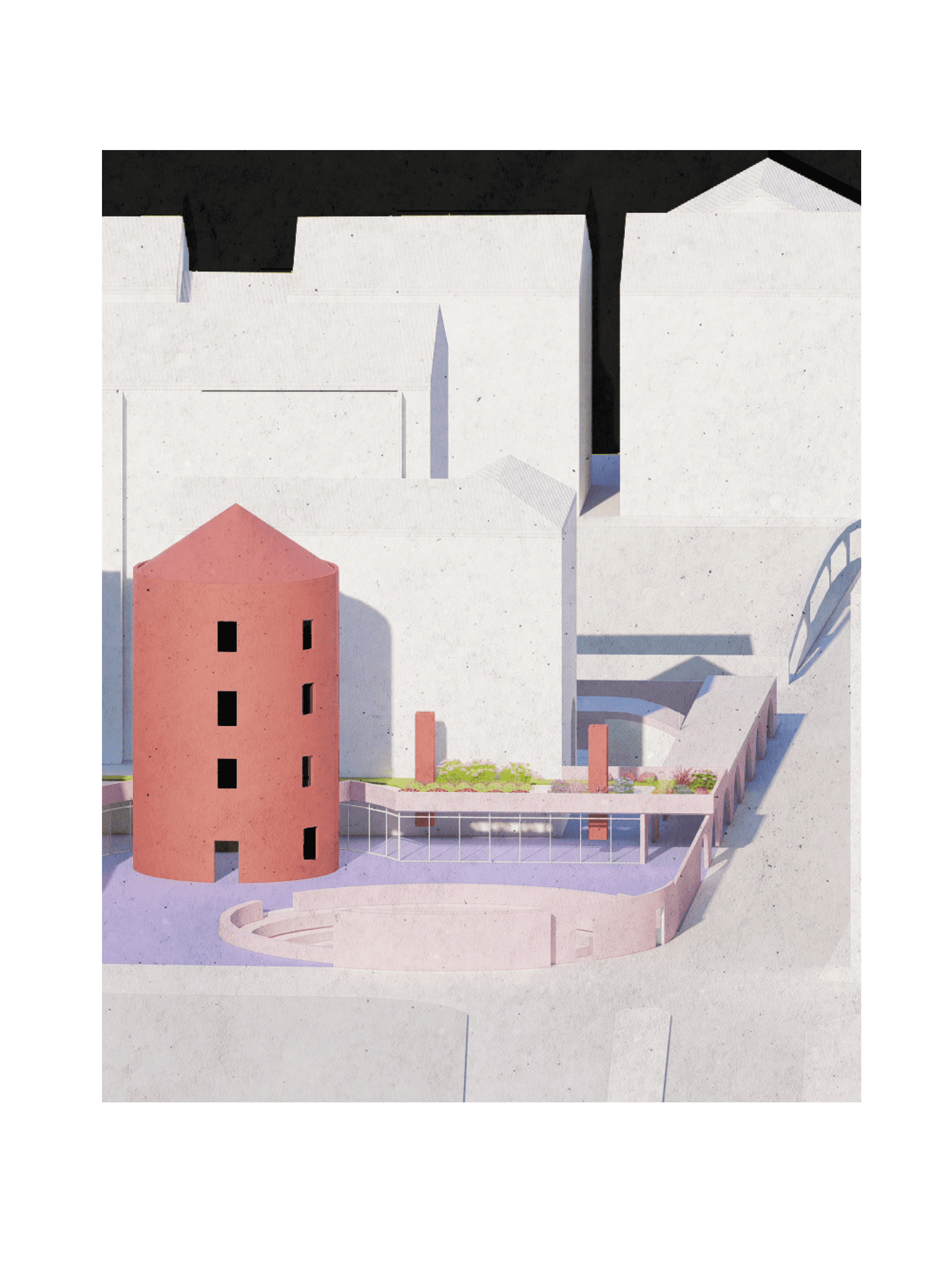

The study looked at the making of civic spaces through the imagination of figurative architectural objects within an empty site facing the Liffey, in Usher’s Island. An amphitheater, a library, and a communal kitchen are placed on the lot and a pedestrian route is reimagined, drawing people within the site and away from the trafficked Bridgefoot Street. The use of figurative and platonic forms of architecture allowed me to not dwell on the typology of the new but rather to focus on how the new buildings acted upon the ground and to imagine how civic life would materialize around them.

Through the process, a hypothesis was formed: an attention to the design of the void space, not merely as the negative of self-referential buildings, but as a building matter that alternates with the built form creating relations and plots, can actively connect the new architecture to the urban tissue that contains it, and prepare it for the unforeseeable metamorphosis that it holds. In this sense, the design of the in-between spaces can become a tool for active open-endedness, and allow the city to be expandable within itself. To be a careful designer of new architectural objects is essential, but to be aware of what they do to the forever-changing city around them is imperative.

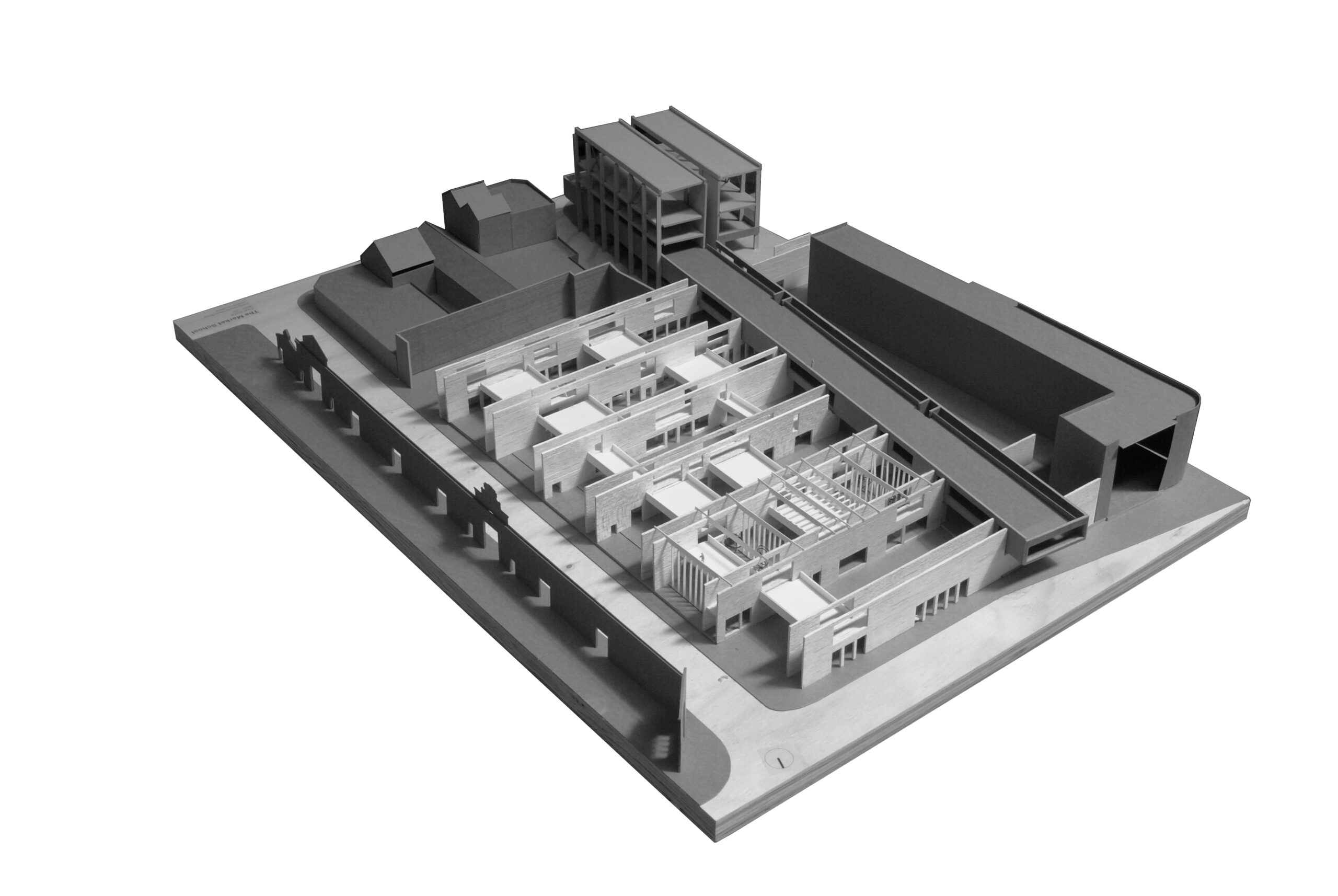

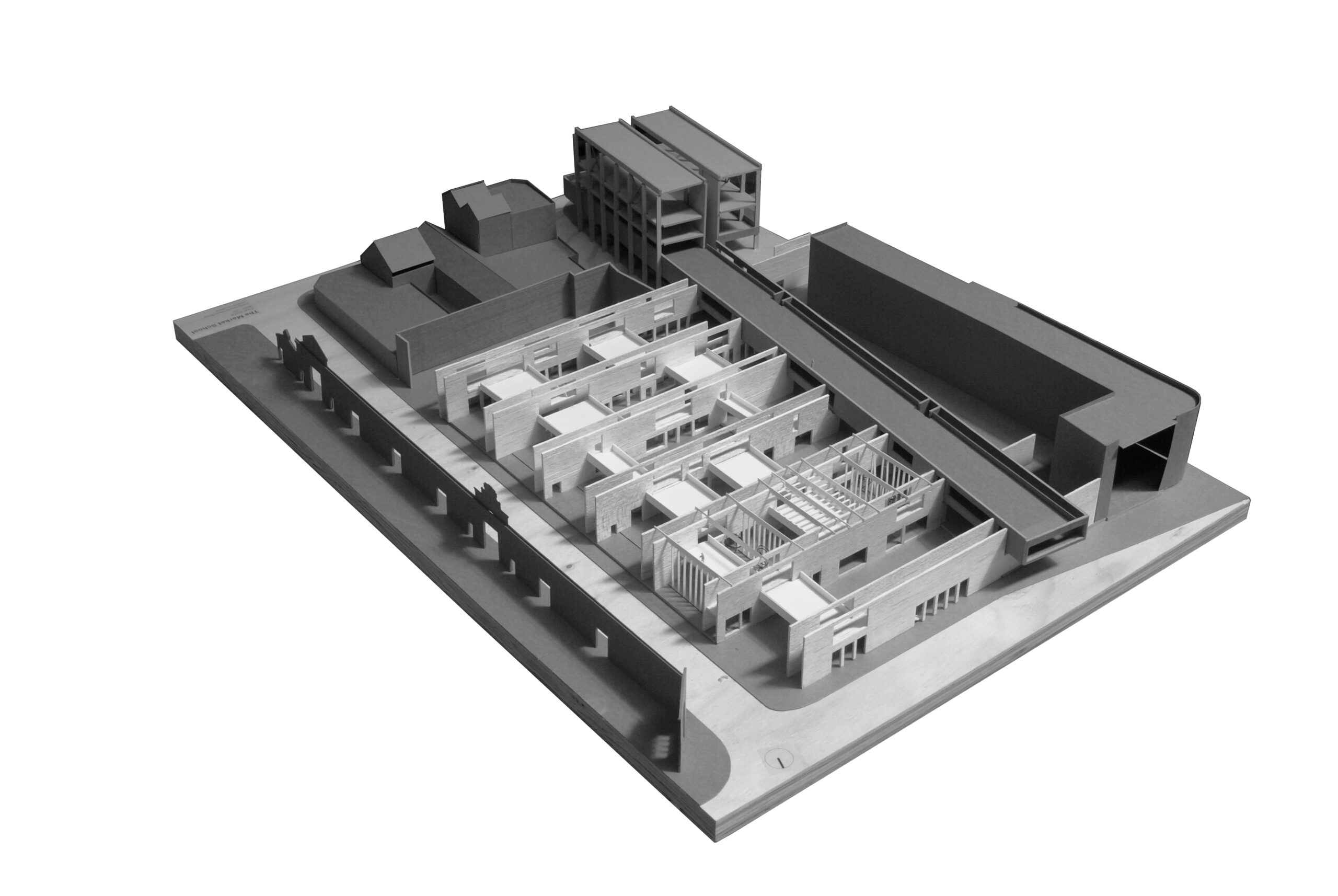

This thesis deals with the tension created between an abandoned existing structure, the memory of a market building and the grain of an existing context. Structure becomes the dominant theme informing the creation of flexible and adaptable learning spaces which respond to both the scale of the person and scale of the city.

School design is a subject in the field of architecture, which should come naturally given that the majority of us spend two decades of our lives in types of institutional buildings. School buildings essentially act as facilitators for learning spaces which, when successful, engage with their surrounding landscape. Many designers like Herman Hertzberger understood their potential, identifying schools as ‘frameworks’ where pupils could develop freely. Hans Scharoun also saw them as a platform for gradual integration into the community without repressing pupils individuality (Blundell Jones, 1997). As places of learning, school buildings should be as inspirational as the inhabitants that use them.

Be it a house, market or school, what is crucial in any design is its negotiation on a number of scales. From the macro or city/landscape scale, to the micro or detail/material scale. This could be called a ‘dialogue’ and happens on multiple levels relating to city, building, material and inhabitants. This ‘dialogue’ is particularly relevant in the design of a school as inhabitants engage with and adapt to the building; as mentioned previously, it is a facilitator for learning.