This thesis aims to explore possible interventions to a common typology in the Irish landscape that could help to alleviate current issues challenging rural society.

Late mediaeval tower houses once dominated and demarcated the island of Ireland into its petty kingdoms and clan holdings. Now they stand as gentle reminders of a chaotic past, when in the name of conquest, cultures combined just as easily as they clashed. What if these crumbling and collapsing structures could be rediscovered and given a new purpose, one which not only preserves the towers themselves and prevents their decay, but gives new life to dwindling agrarian communities and inspires renewed vigour in the Gaelic traditions and culture they once were so tied to?

This thesis invisions that the chosen project site Renvyle Castle, Co. Galway could serve as a prototype for a nascent towerhouse intervention typology through which a successful combination program can be reinserted and replicated at many similar sites throughout the landscape. Ultimately the core philosophy of this thesis is that ‘using is maintenance’, that by reprogramming and giving purpose to rapidly decaying structures they may be preserved in their current state for future generations in a way that is reversible and not utterly transformative as is seen in restoration projects.

Listed monuments are in a sort of maintenance limbo whereby they must either be restored using period correct materials and techniques or left alone to crumble into obscurity. This thesis aims to provide a possible alternative to the tedious, expensive, and thankless job of restoring a tower house. The tower houses ubiquity amongst the Irish midlands and west coast provides an excellent opportunity to not only develop upon a thriving tourist industry but to highlight and preserve their importance to the fabric of the landscape as they stand, in varying states of ruin.

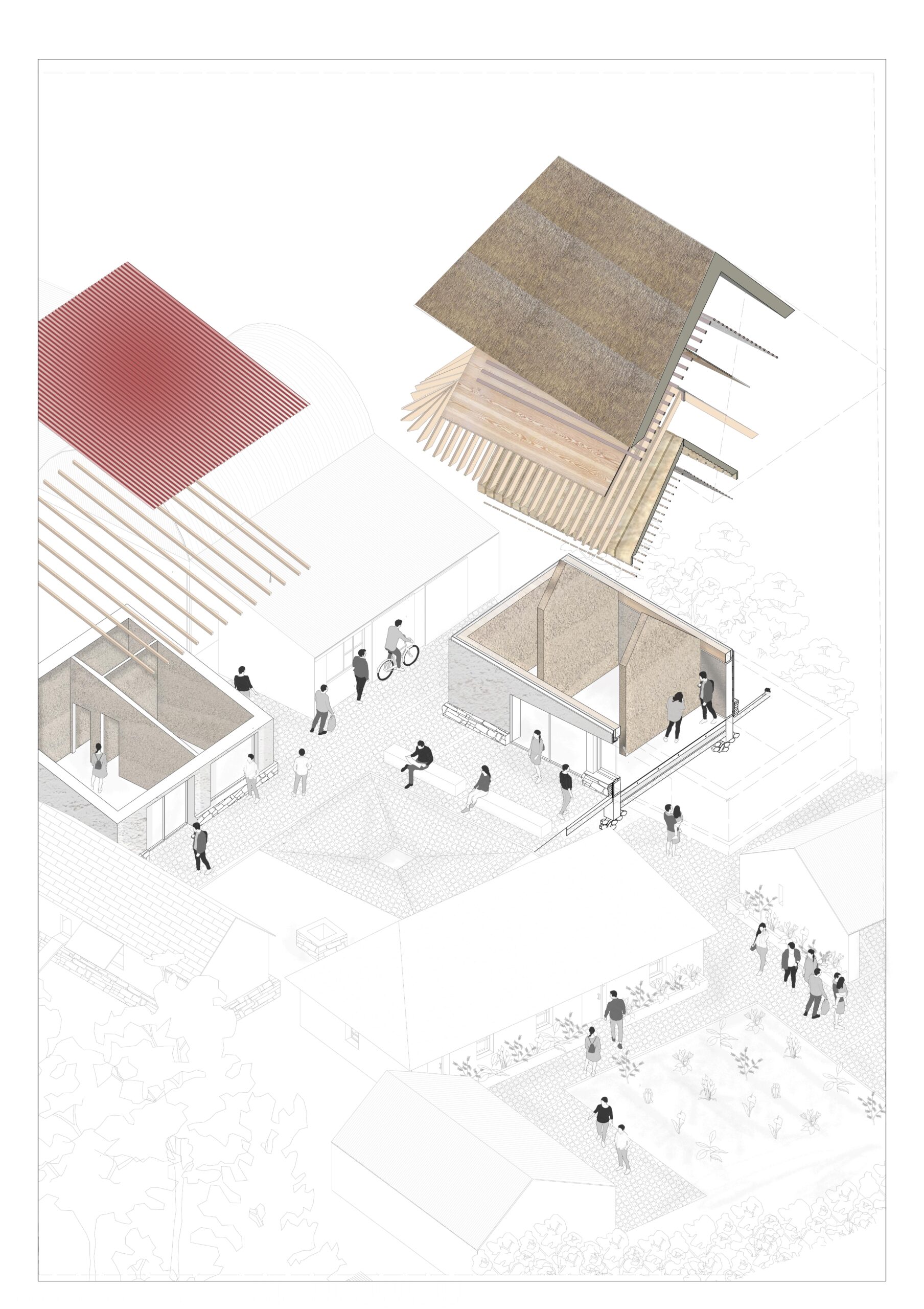

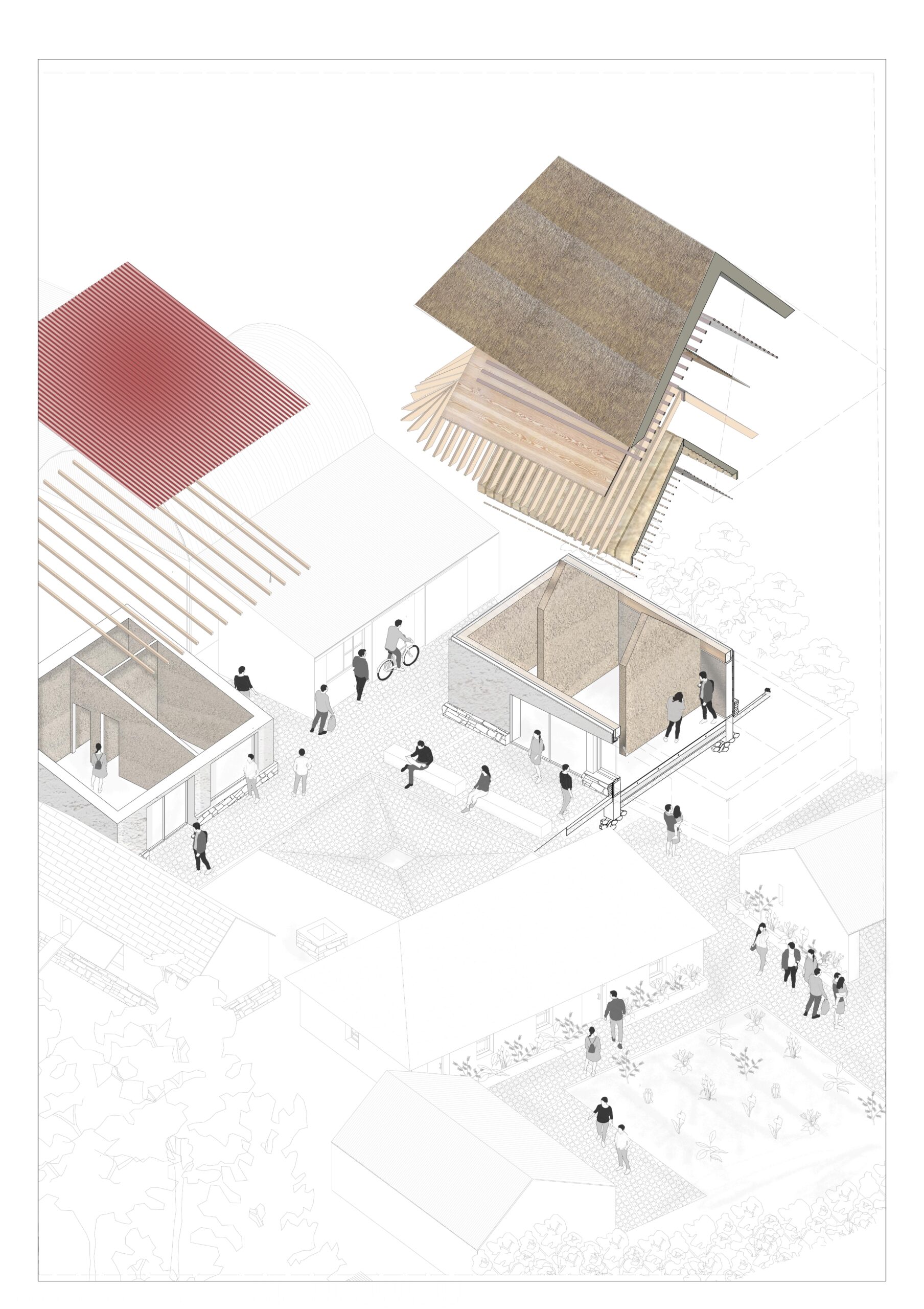

This thesis explores the potential of Irish vernacular architecture to inform modern sustainable practices, particularly in rural Ireland. It delves into the rich heritage of traditional Irish buildings, which were constructed using local materials like stone, wood, and thatch, and were designed to harmonize with the environment. These structures are more than just physical spaces; they embody a way of life that connects deeply with the land and community. The research argues for the rehabilitation and adaptation of these traditional structures as a means to address contemporary challenges such as rural depopulation, loss of cultural identity, and the environmental impact of modern construction. By preserving the original craftsmanship while integrating modern amenities, these buildings can be revitalized to reduce the carbon footprint associated with new construction and enrich the cultural landscape. A key part of the thesis is a design proposal for a site in Tourin, Co. Waterford. This traditional farm courtyard, currently in ruins, is envisioned as a center for research and education on vernacular architecture. The project aims to create a living example of how traditional construction methods can be adapted for modern use, serving as a hub for learning and preserving these practices for future generations. The thesis also explores how traditional building materials can be used innovatively in new construction to meet modern sustainability standards. By revisiting these materials, such as water reeds and thatch, the research highlights their relevance in addressing today’s environmental challenges. In essence, this thesis is a call to action for the preservation and development of Ireland’s vernacular architectural heritage. It emphasizes the value of learning from the past to create sustainable, culturally rich homes and communities that are deeply connected to the landscape.

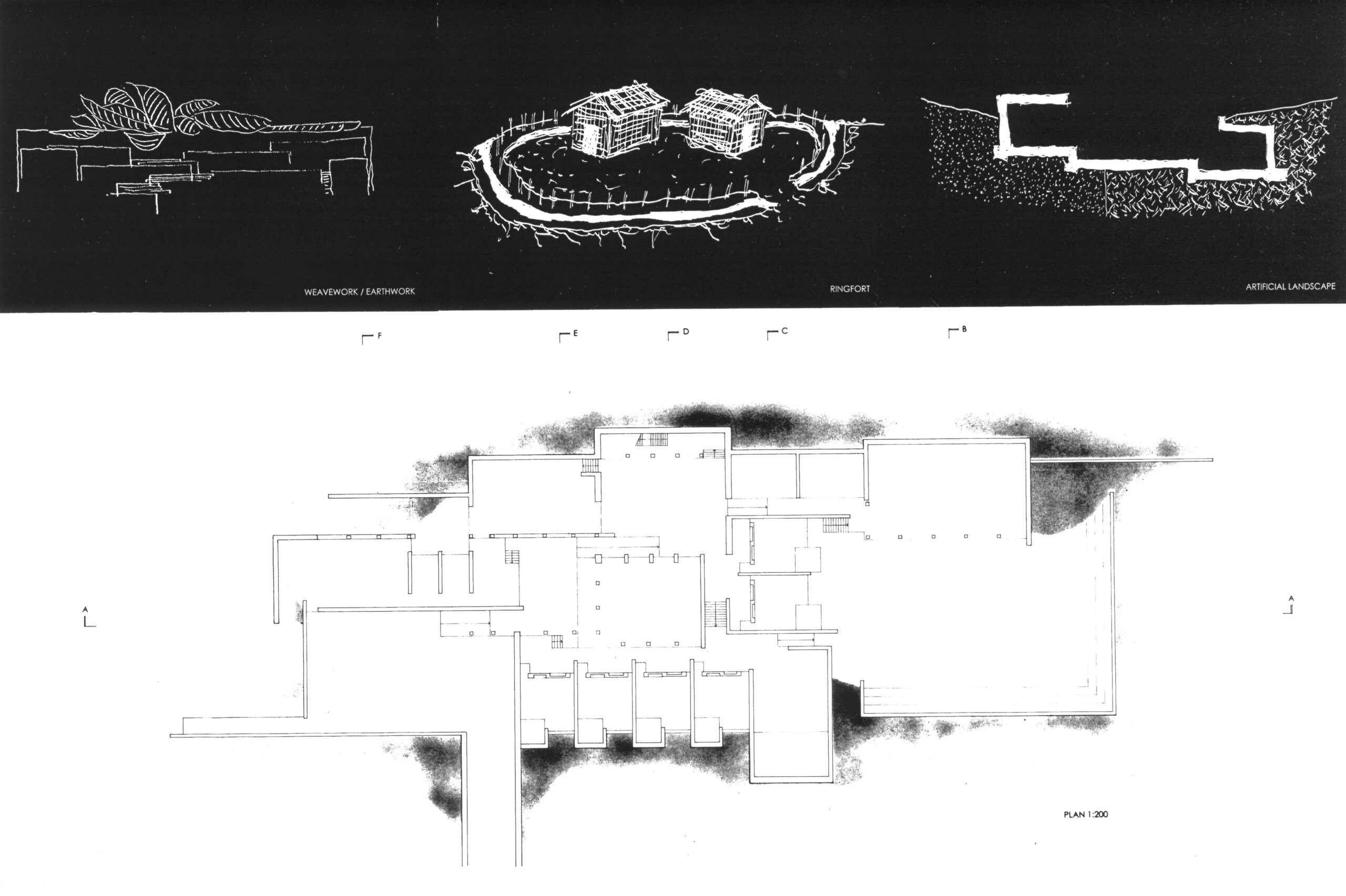

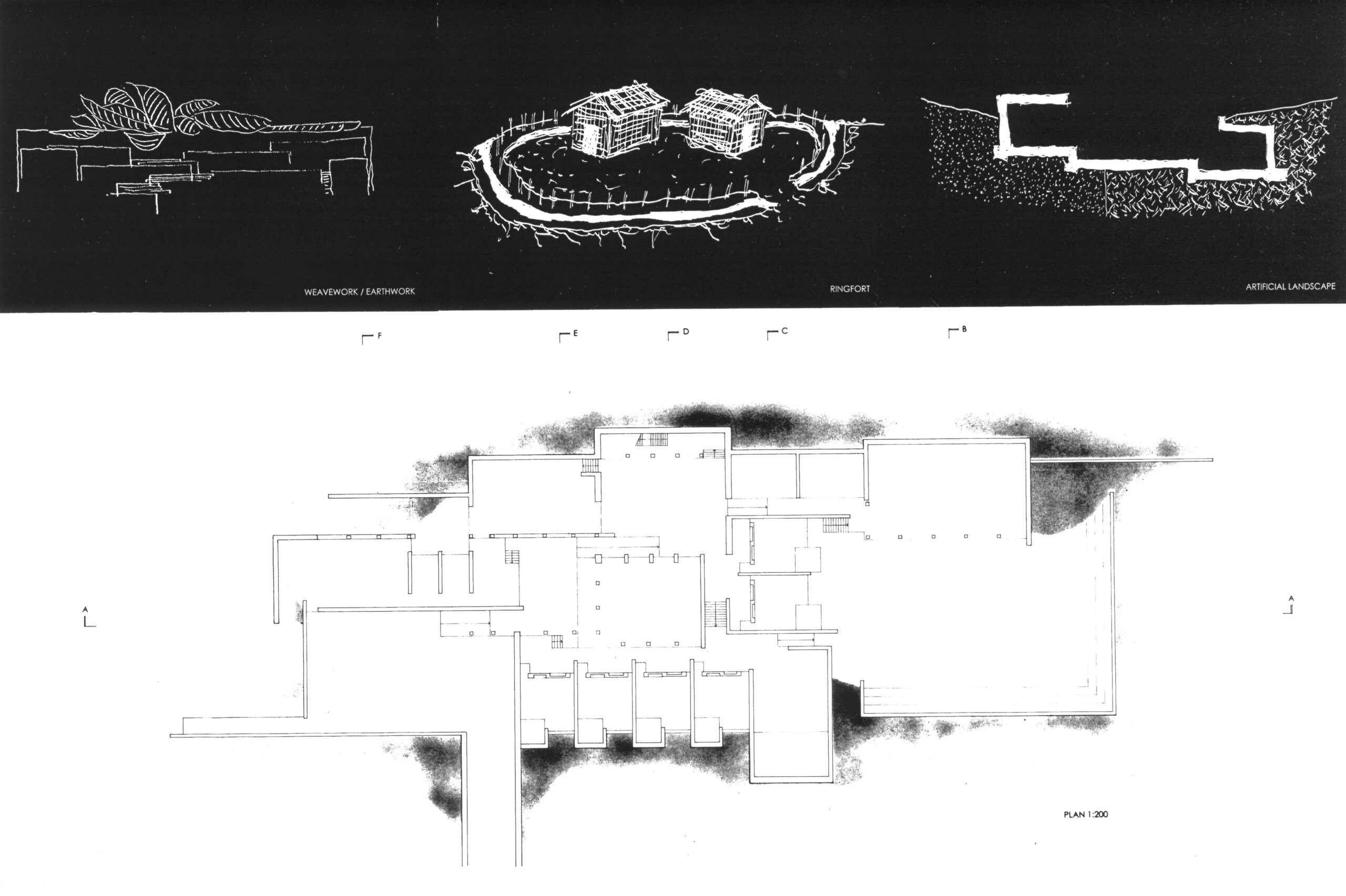

I have been exploring the Sligo ground.

Exploring the ground as a deposition of a multiplicity of narratives and texts, ranging from mythology, to archaeology, to geology, to the poetry of Yeats, to contemporary tourist brochures.

Exploring the ground as a source of discovered space.

Exploring the ground as a source of meanings that can be transformed and connected to through building. The act of building must, of its essence, mark the ground, depositing another layer of representation and adding to the complex multiplicity of readings with which this ground is imbued.

I have been exploring how this can be achieved in a meaningful way so as to achieve a resonance with this place.

The house project is sited in the amazing Glen which cuts through the terrain for a mile and a half on the south side of Knocknarea, and which was written about by Yeats. The project was about responding to this by making an incision into the ground. In this way the form of the building was made by this manipulation of the ground and then a series of tectonic planes were added to articulate the spaces and control the views through and across these spaces to the wider landscape.

The subject for the thesis is then a community school and the site is on the other side of Knocknarea, just above Strandhill. The site is located where the field system breaks down and the mountain begins, and is also on a stratigraphical boundary where the hard limestone of the mountain changes to the softer rock and shale below. There are two eighth or ninth century ringforts adjacent to the site.

The thesis has therefore been an exploration of how to achieve a resonance with this place and with these narratives that are contained in this ground. I have attempted to make this artificial landscape using concrete as a kind of third geology, that is inserted between the two landscapes and begins to act as a threshold between them, with one side being buried and the other built up to respond to the different edges.

This thesis explores the notion of weaving in both a physical and social sense. The textile becomes a multi-faceted motif, a driving force in the activity of a place as well as an influence on its built form. I started to think about this idea in the context of Galway with its own history of textiles, as it became a means of threading aspects of the project together. Inherent in it is the value in interconnectivity, of architectural elements, old and new built fabric, occupants and social structures. It is these confluences that make up the thesis.

The site consists of a former distillery and textile factory and its surroundings on Nun’s Island. Embodying a forgotten industrial heritage, the distillery sits across the Corrib, viewable but unapproachable. The scheme bridges this connection in an initial strategic move that sets up an atmosphere of passing through or of overlooking distant spaces.

The aim is to weave university and city by establishing an isolated NUIG campus closer to the city, giving their research institutes a central position from which to engage with the public. The building values the transparency of knowledge, providing chances of encounter between disciplines throughout. This townhouse for Galway is university infrastructure and civic amenity at once.

This theme of transparency is reflected in the architectural approach as veil like screens bind old and new fabric. The transparent screen is used as a device to reveal and conceal connections. In places, it affords the reading of old alongside new, in others it lightly partitions off spaces.

The overall ambition of this adaptive-reuse and regeneration project was to inject new life through careful architectural intervention into the currently overlooked, and underutilised area of the Stranmillis campus around the Henry Garrett building. This is accomplished through the partial adaptive reuse of the Henry Garrett building, and the intervention of a loggia to activate the central, overlooked meadow space as an informal courtyard. The architectural challenges of this site included, the poor utilisation of the existing natural environment, partly due to the imposing road network throughout the campus that limits pedestrian movement around it. The relative lack of formal public areas for socialising and working, which include the stunning woodland and grass areas around the campus which create opportunities for informal social spaces, however they are not utilised due to the poor spatial layout of the campus, with disconnected buildings and pedestrian paths intercepted by roads. And finally, the fact that the Henry Garrett building itself, a Grade B+ listed red brick former multi purpose educational building, constructed in the late 1940’s, is laying derelict, in a state of disrepair.

The renovation of this building could be a key intervention into unlocking the overlooked potential of the campus, as well as being crucial to preserving, and continuing to utilise the unique built heritage of Belfast. The success of the proposed intervention should re-animate this area into a socially cohesive, engaged space that will be utilised by future generations. The interventions are designed to outlast the Henry Garrett building, therefore as the existing fabric of the building further disintegrates over time, the intervention will remain, redefining the spatial alignment of the space to be shaped by future generations.

“Every building must create coherent and well-shaped public space next to it”(Christopher Alexander, in “A New Theory of Urban Design” 1987)