This thesis explores the notion of weaving in both a physical and social sense. The textile becomes a multi-faceted motif, a driving force in the activity of a place as well as an influence on its built form. I started to think about this idea in the context of Galway with its own history of textiles, as it became a means of threading aspects of the project together. Inherent in it is the value in interconnectivity, of architectural elements, old and new built fabric, occupants and social structures. It is these confluences that make up the thesis.

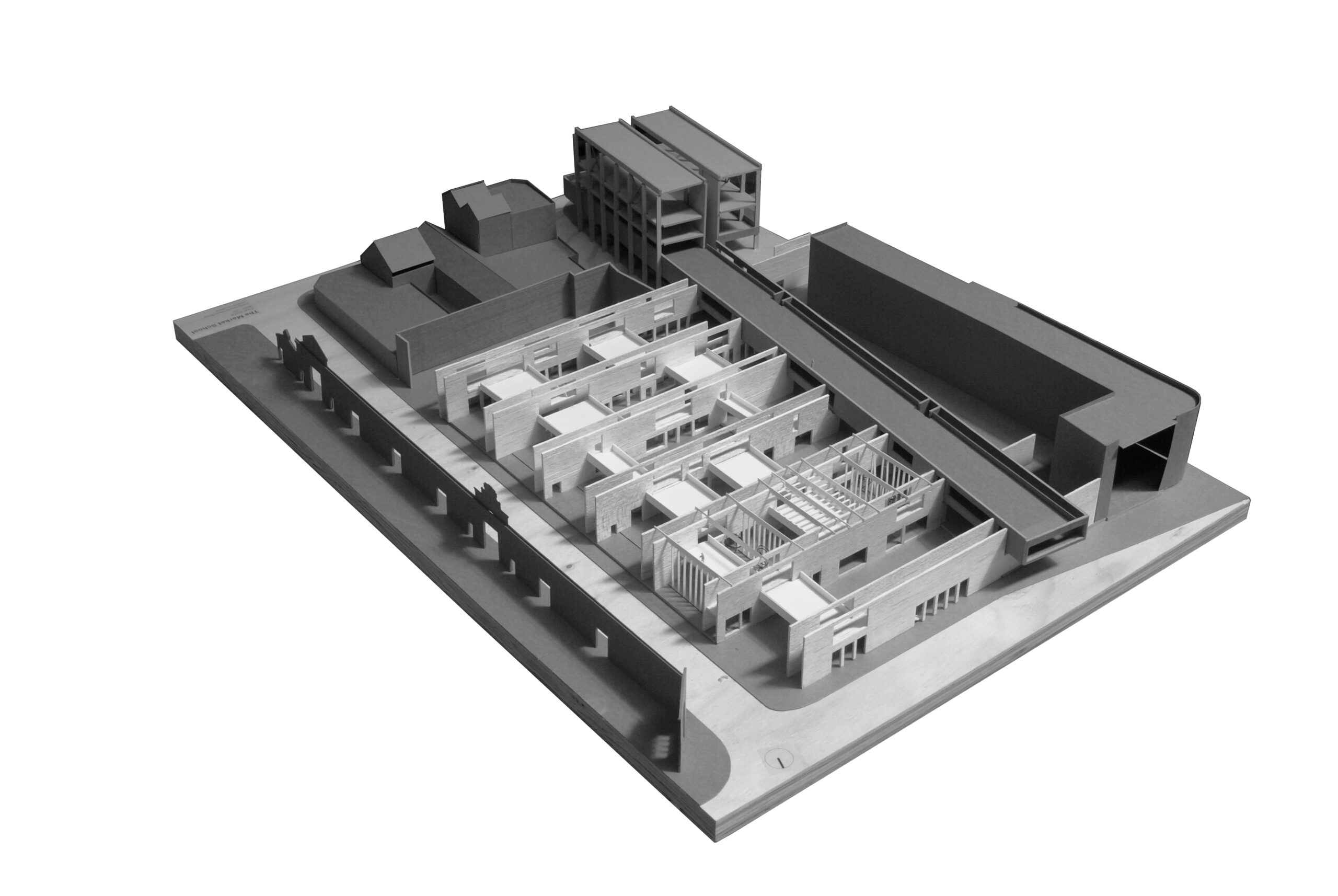

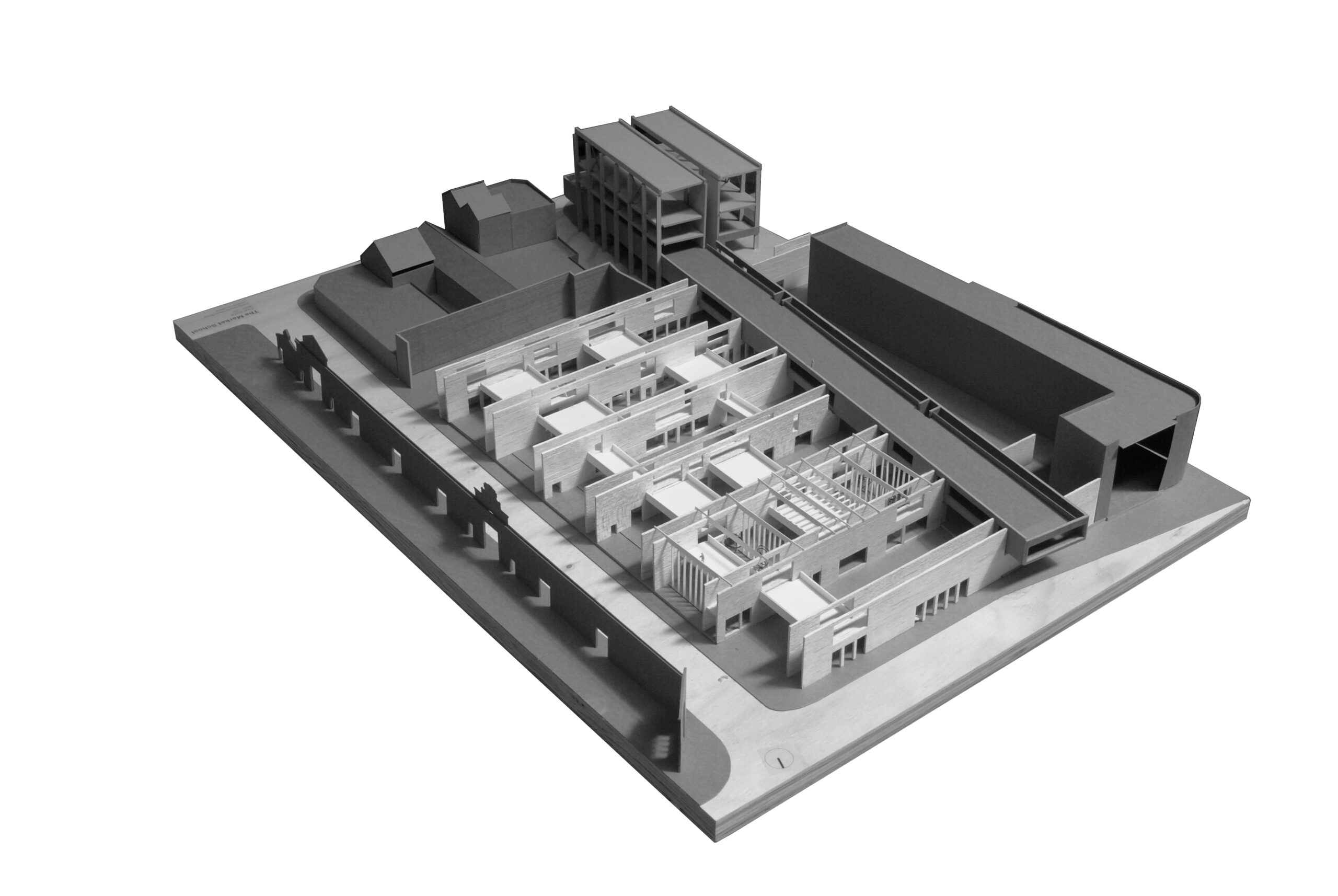

The site consists of a former distillery and textile factory and its surroundings on Nun’s Island. Embodying a forgotten industrial heritage, the distillery sits across the Corrib, viewable but unapproachable. The scheme bridges this connection in an initial strategic move that sets up an atmosphere of passing through or of overlooking distant spaces.

The aim is to weave university and city by establishing an isolated NUIG campus closer to the city, giving their research institutes a central position from which to engage with the public. The building values the transparency of knowledge, providing chances of encounter between disciplines throughout. This townhouse for Galway is university infrastructure and civic amenity at once.

This theme of transparency is reflected in the architectural approach as veil like screens bind old and new fabric. The transparent screen is used as a device to reveal and conceal connections. In places, it affords the reading of old alongside new, in others it lightly partitions off spaces.

This thesis deals with the tension created between an abandoned existing structure, the memory of a market building and the grain of an existing context. Structure becomes the dominant theme informing the creation of flexible and adaptable learning spaces which respond to both the scale of the person and scale of the city.

School design is a subject in the field of architecture, which should come naturally given that the majority of us spend two decades of our lives in types of institutional buildings. School buildings essentially act as facilitators for learning spaces which, when successful, engage with their surrounding landscape. Many designers like Herman Hertzberger understood their potential, identifying schools as ‘frameworks’ where pupils could develop freely. Hans Scharoun also saw them as a platform for gradual integration into the community without repressing pupils individuality (Blundell Jones, 1997). As places of learning, school buildings should be as inspirational as the inhabitants that use them.

Be it a house, market or school, what is crucial in any design is its negotiation on a number of scales. From the macro or city/landscape scale, to the micro or detail/material scale. This could be called a ‘dialogue’ and happens on multiple levels relating to city, building, material and inhabitants. This ‘dialogue’ is particularly relevant in the design of a school as inhabitants engage with and adapt to the building; as mentioned previously, it is a facilitator for learning.