For a person who can’t even play football, a soccer stadium might seem like a strange choice of programme for a thesis. But when I began the project at the start of 1992, following an initial semester of group work focused on the “western gateway” to the city, around Heuston Station, the country was still basking in the glory of our exploits at Italia ’90. Most of all, a stadium seemed to me to be a valid vehicle – a large building, full of people – for the pursuit of a thesis on architecture.

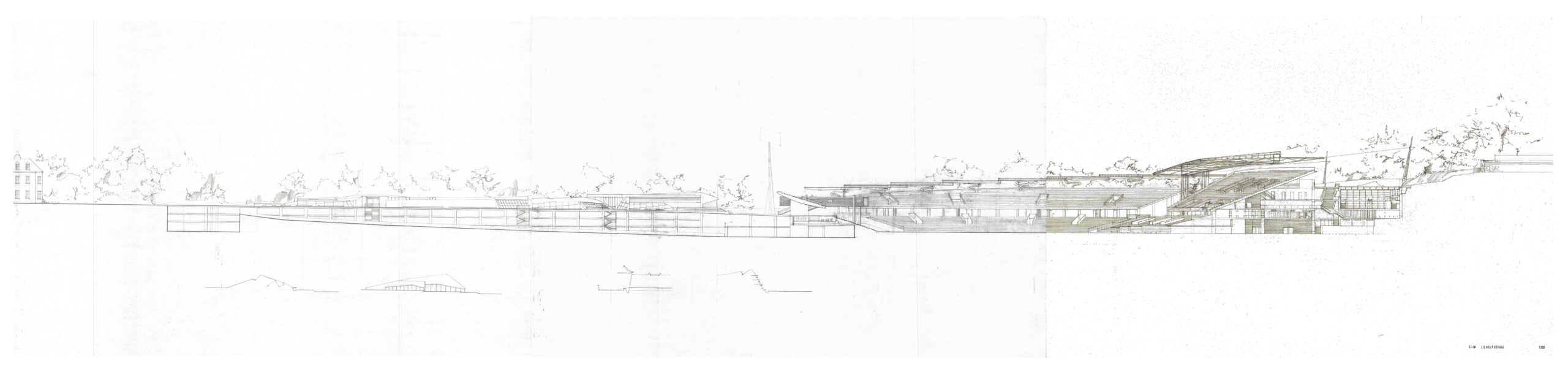

I could concentrate on structure and space, physical context and topography, while at the same time, perhaps indirectly, invoking history, urbanism and society. The site, roughly in the original location of St. James’ Gate, occupies the east-facing slope leading down from the Royal Hospital Kilmainham to Dr. Steeven’s Hospital [both C17th buildings] and the entrance to Heuston Station.

Most stadia are approximately symmetrical, but the sloping site presented me with an unavoidably asymmetrical stadium. Looking for a reference for this, I started with the 12 stadia built specifically for Italia ’90 – in the end I found a stadium outside Madrid called “la Peineta” by Cruz y Ortiz. This is a large concrete plate on one side, to provide seating, supported on three concentric concrete walls below.

I adapted this idea to the St. James’ site, the concentric walls directing traffic in from the main road into an underground car-park. Above this internal “road”, the top-lit “canyon” formed between the concrete walls and the hillside contained all of the changing rooms and hospitality functions. The main body of seating sat on top of the walls [as per Cruz y Ortiz], fed by staircases from below, and covered by a large roof following the angle of the slope and supported by an 80-metre arched truss, spanning from north to south ends.

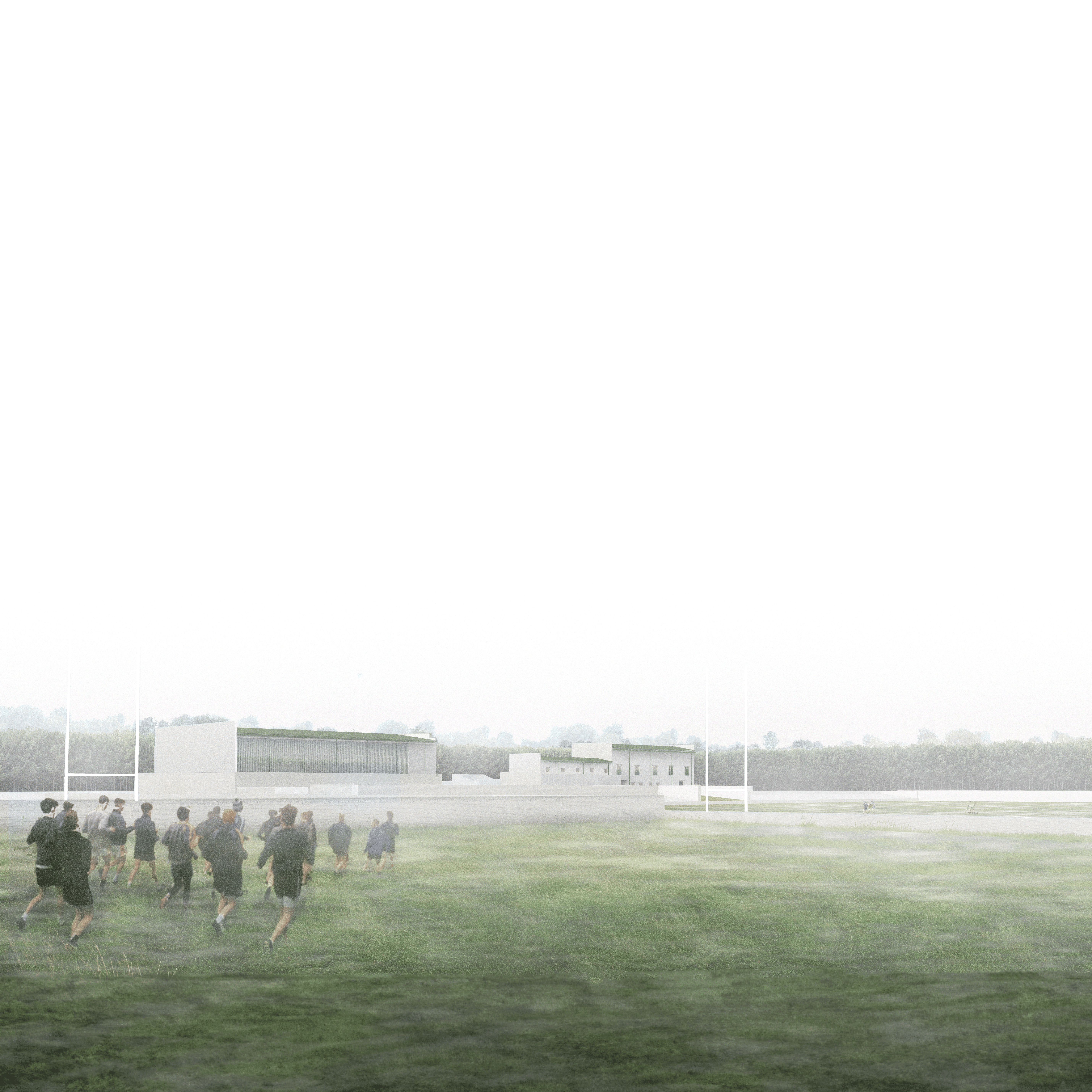

At the eastern side of the site, an open-to-air smaller tribune, provides seating facing west. Behind this, a covered coach-park and main pedestrian access, appears from above as a landscape of varied smaller roof forms, like scattered leaves. Total capacity is 65,000 seats.