In suburbia, the morphology of the housing estate monopolises programme.

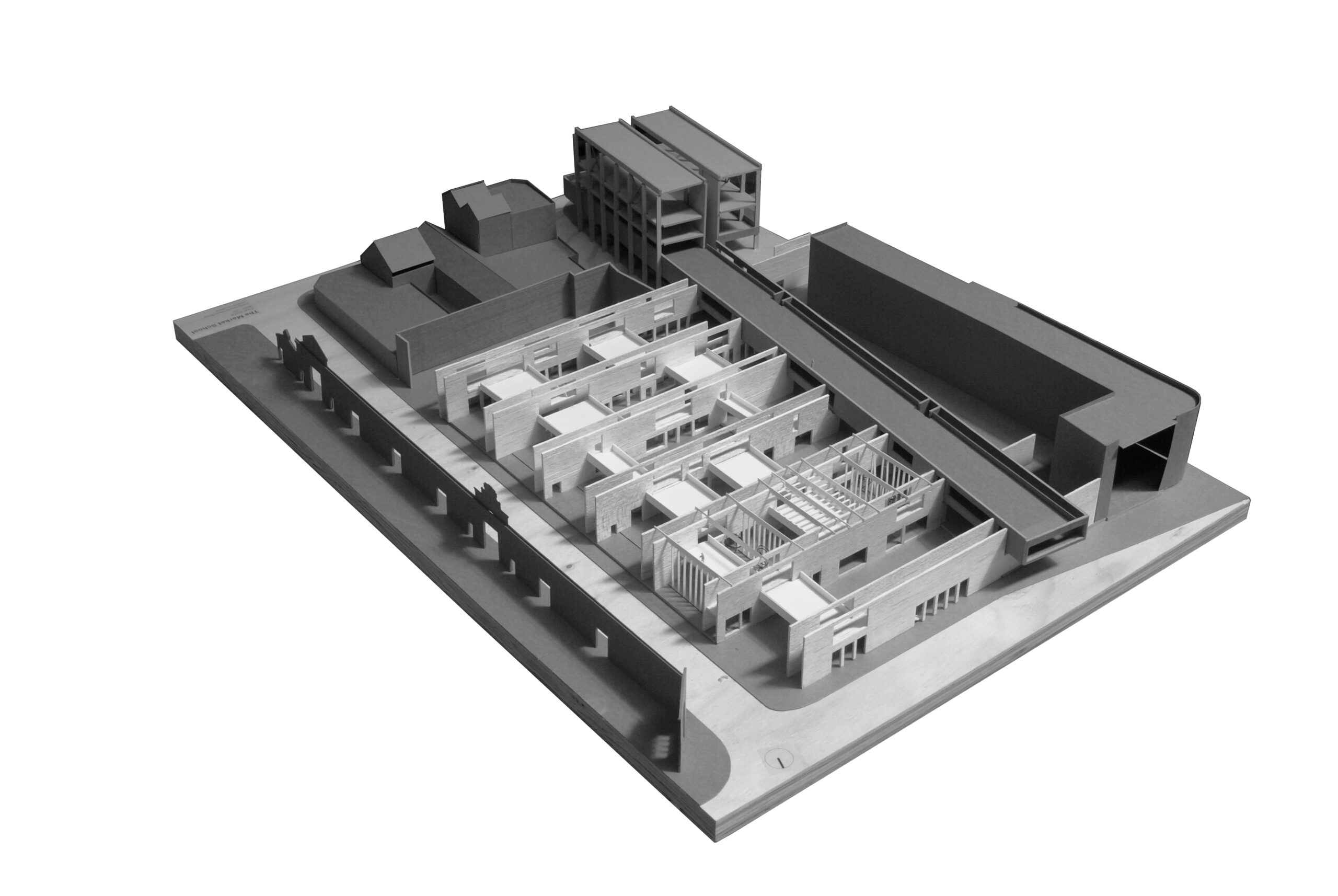

The sub-division of land, the layout of streets and the essential relationship of public and private worlds is determined by the dimensional repetition of the semi-d. In between are interspersed the basic infrastructures for survival – the petrol station, the newsagent, the amorphous green space. Such rare interruptions in function are equally a break in the dominant spatial order of the three-bedroom plot. These gaps in the dominant residential programme present an opportunity.

Distanced from the centres and avoiding the pressures of commerce, the former use value of the old city has emigrated with the citizenry to the suburbs. Despite this there remains a missing component to suburban life – the civic space. In the oversized or oddly shaped green spaces are the greatest opportunities for the civic in urban life. Free of fences, closing hours, by-laws or even function these afterthoughts may be the contemporary commons.

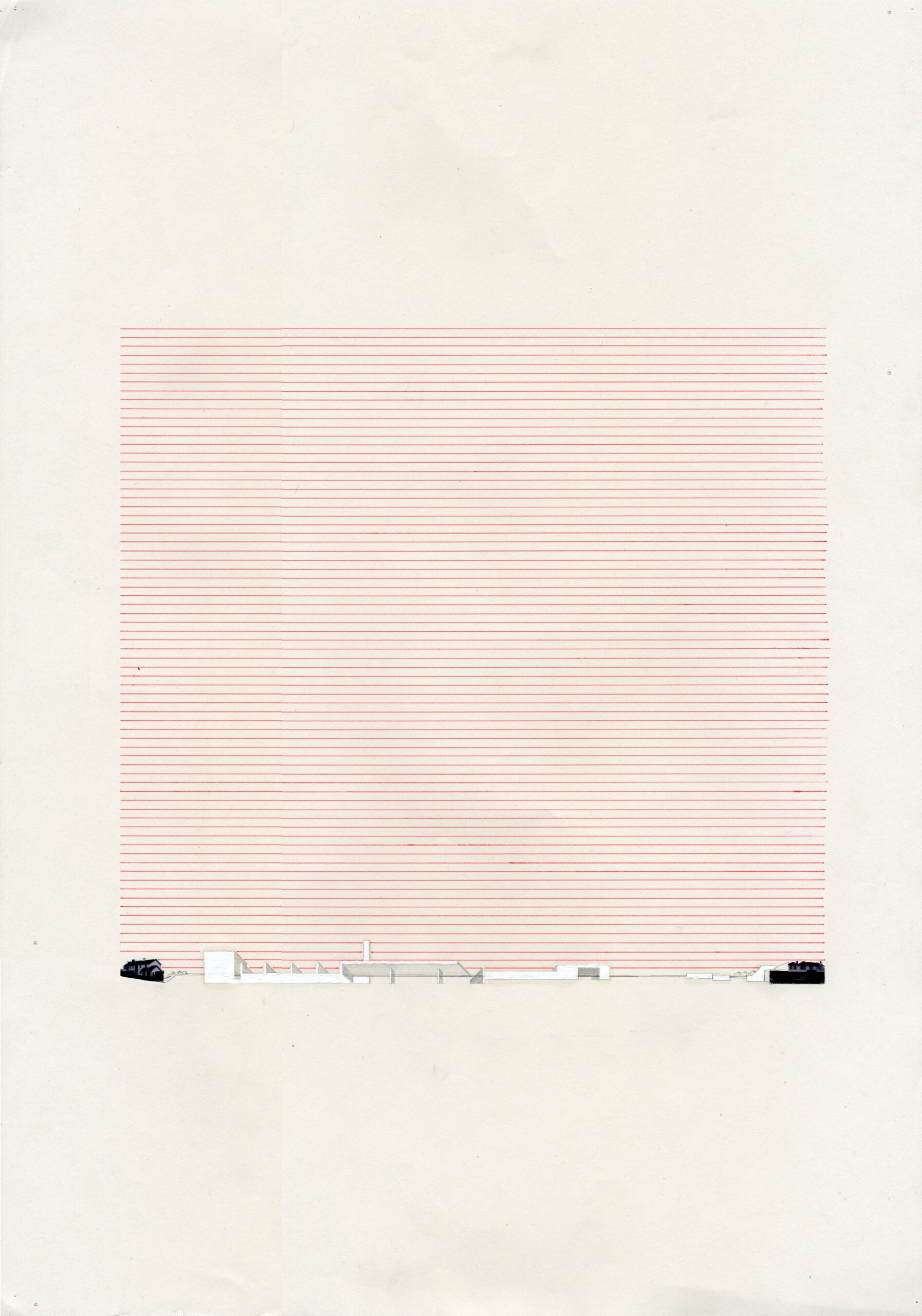

For a successful civic space to take root in suburbia, one cannot resort to the simple insertion of urban or rural typologies. Within the confines of the suburban daily routine there is space for an architecture. The answer lies within the rhythms of commuting, school terms and the occasional birthday party. Equally, it is essential to acknowledge the unique size and shape of the green patch in juxtaposition to the constraints of the housing plot. This break from residential form and function allows for a public scale of intervention. In other words , the possibility to give inhabitants the spaces for living that their private homes could never fulfil. Within these limits there is an opportunity, not to force a change in people’s lives but to make sublime how we already live.