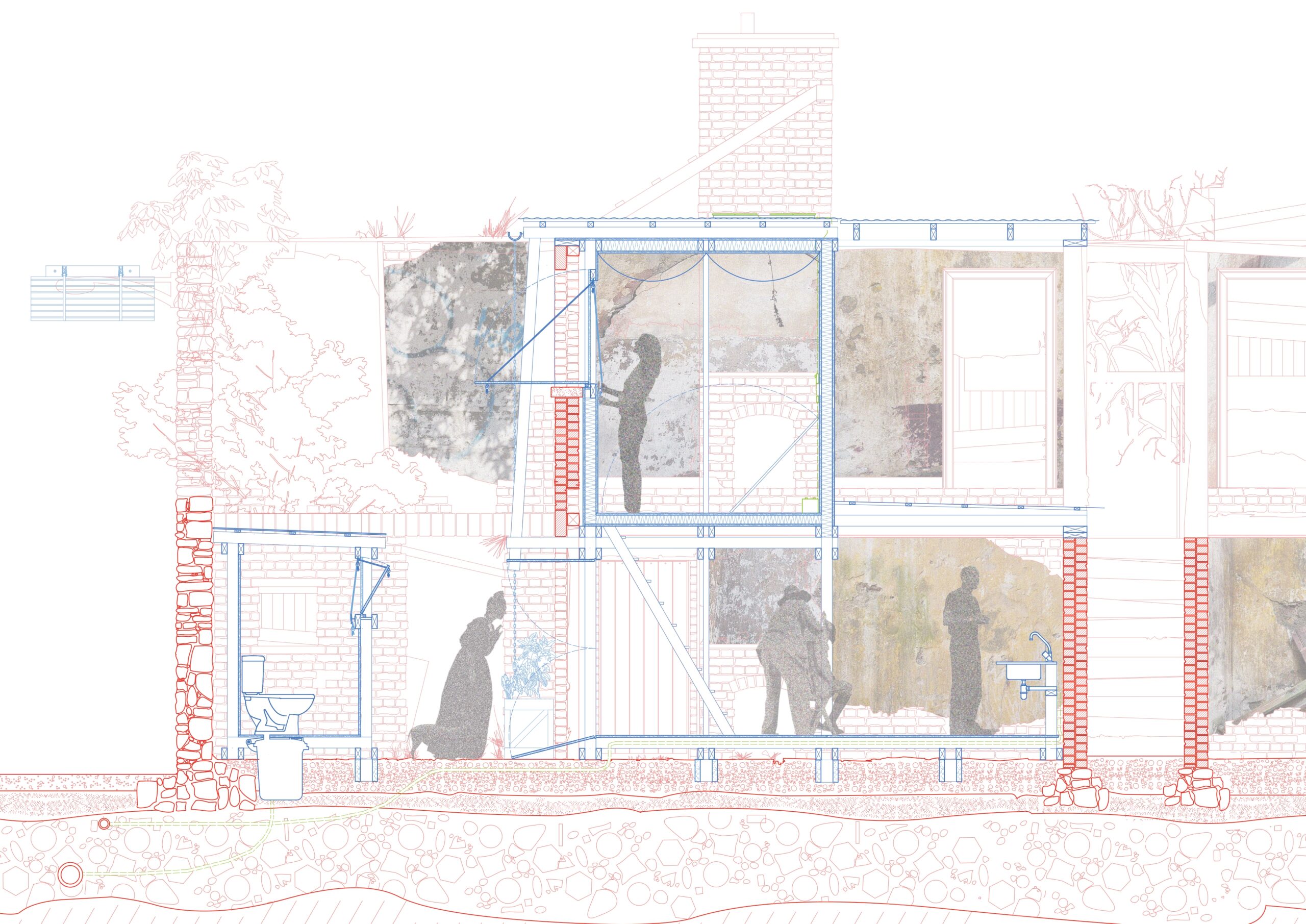

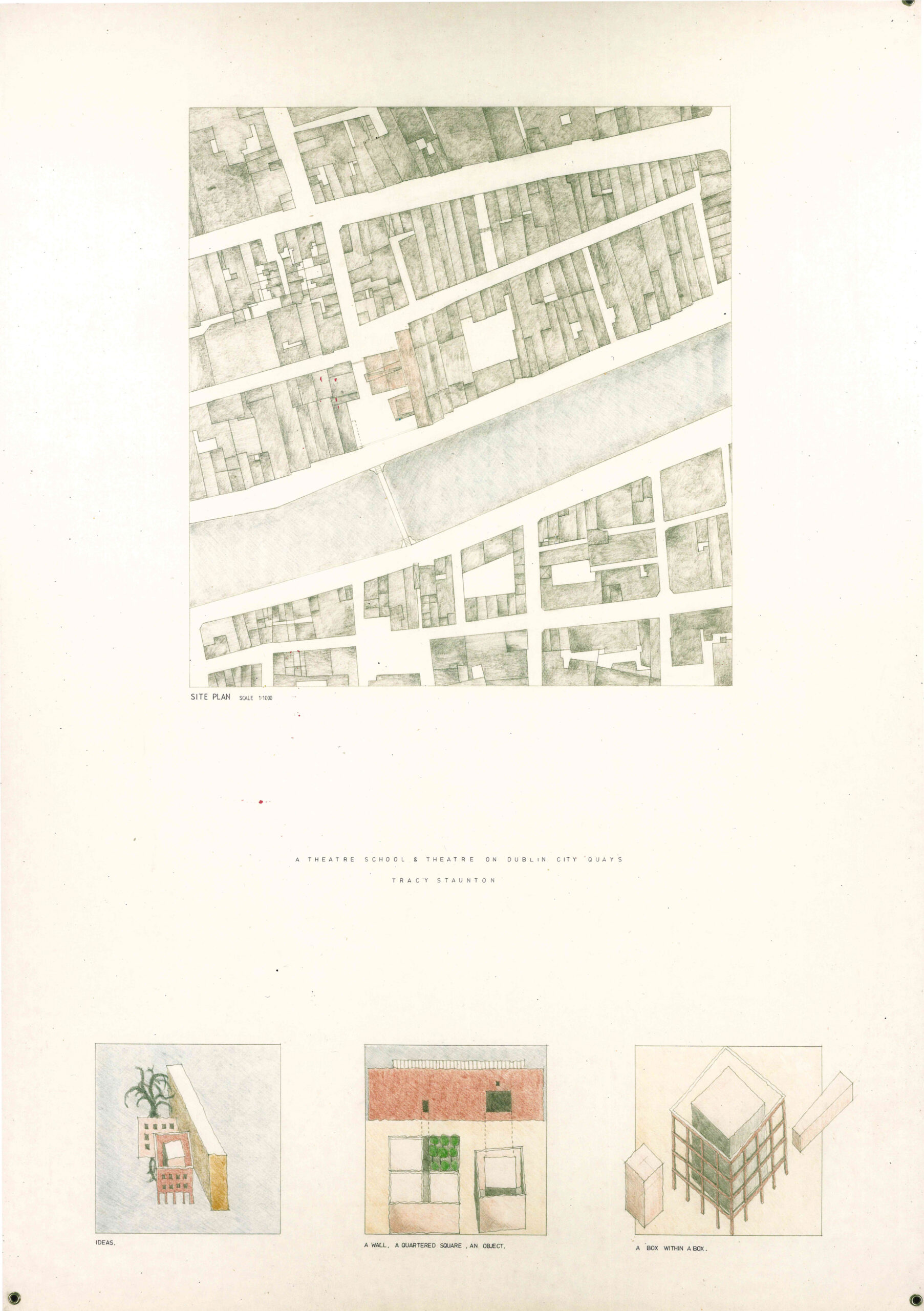

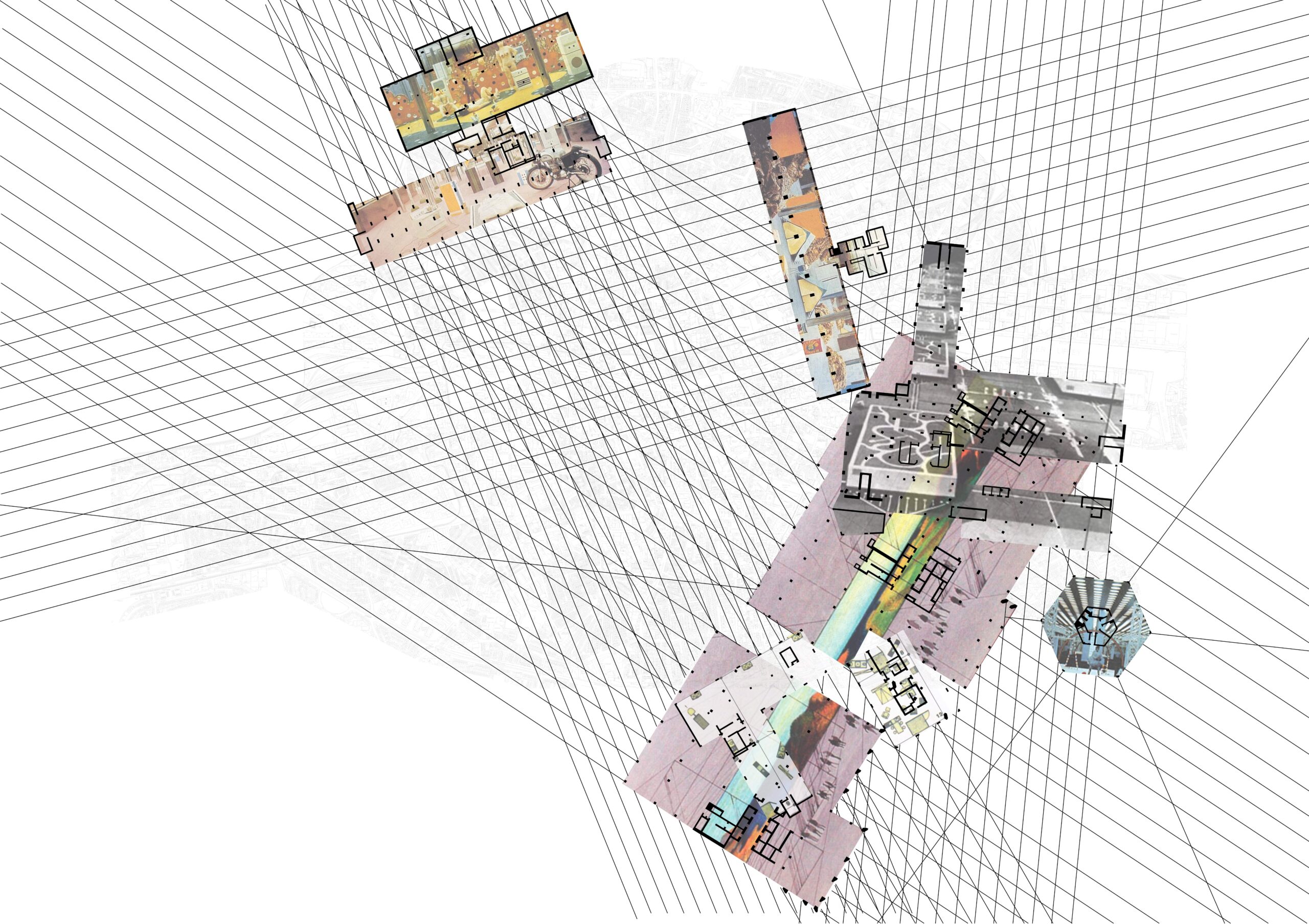

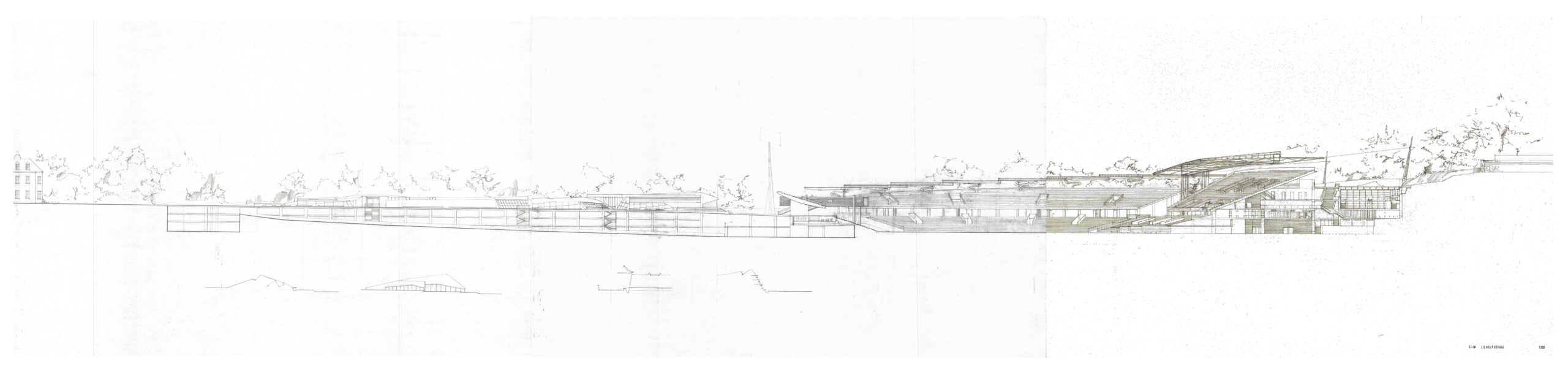

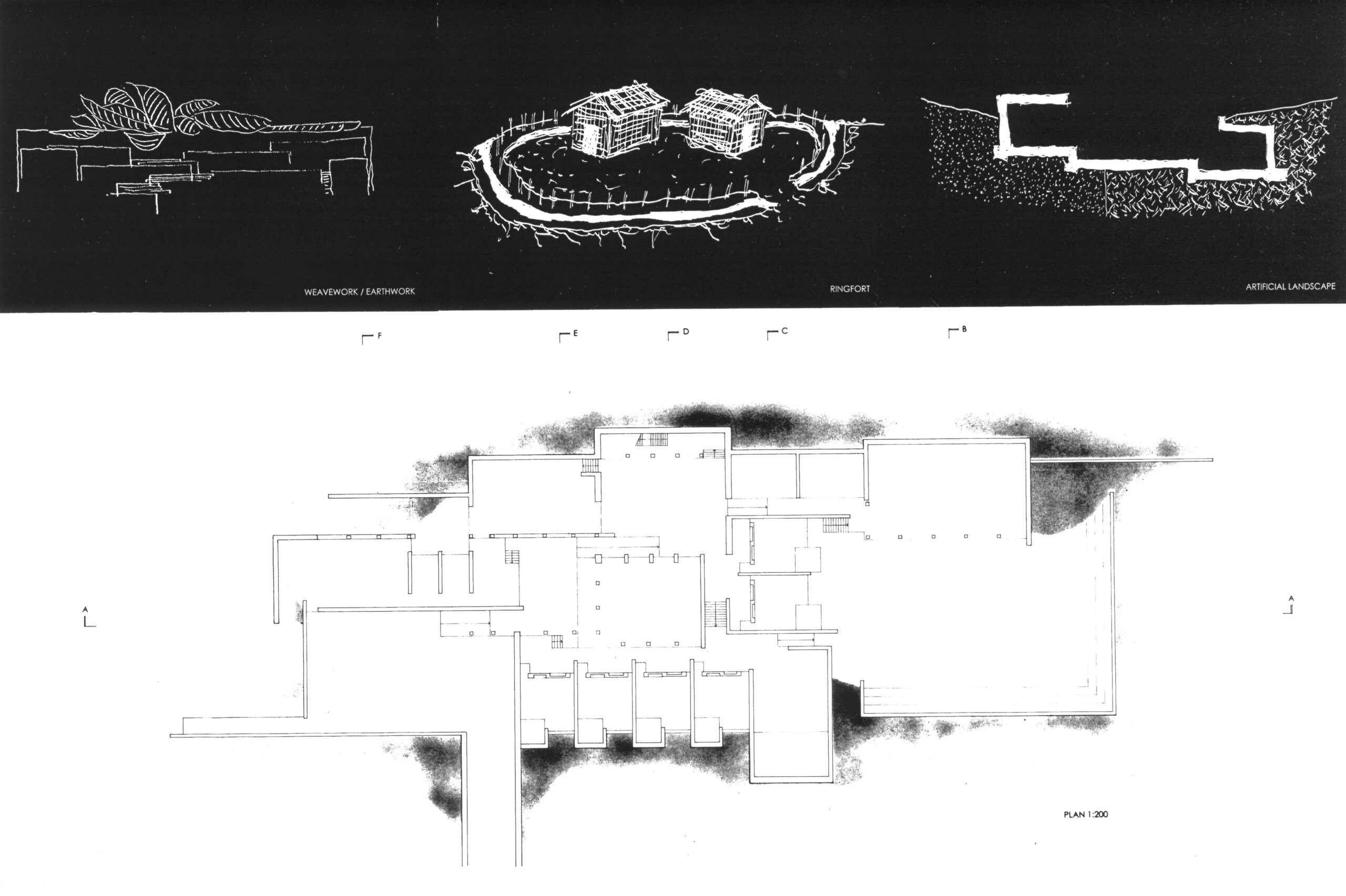

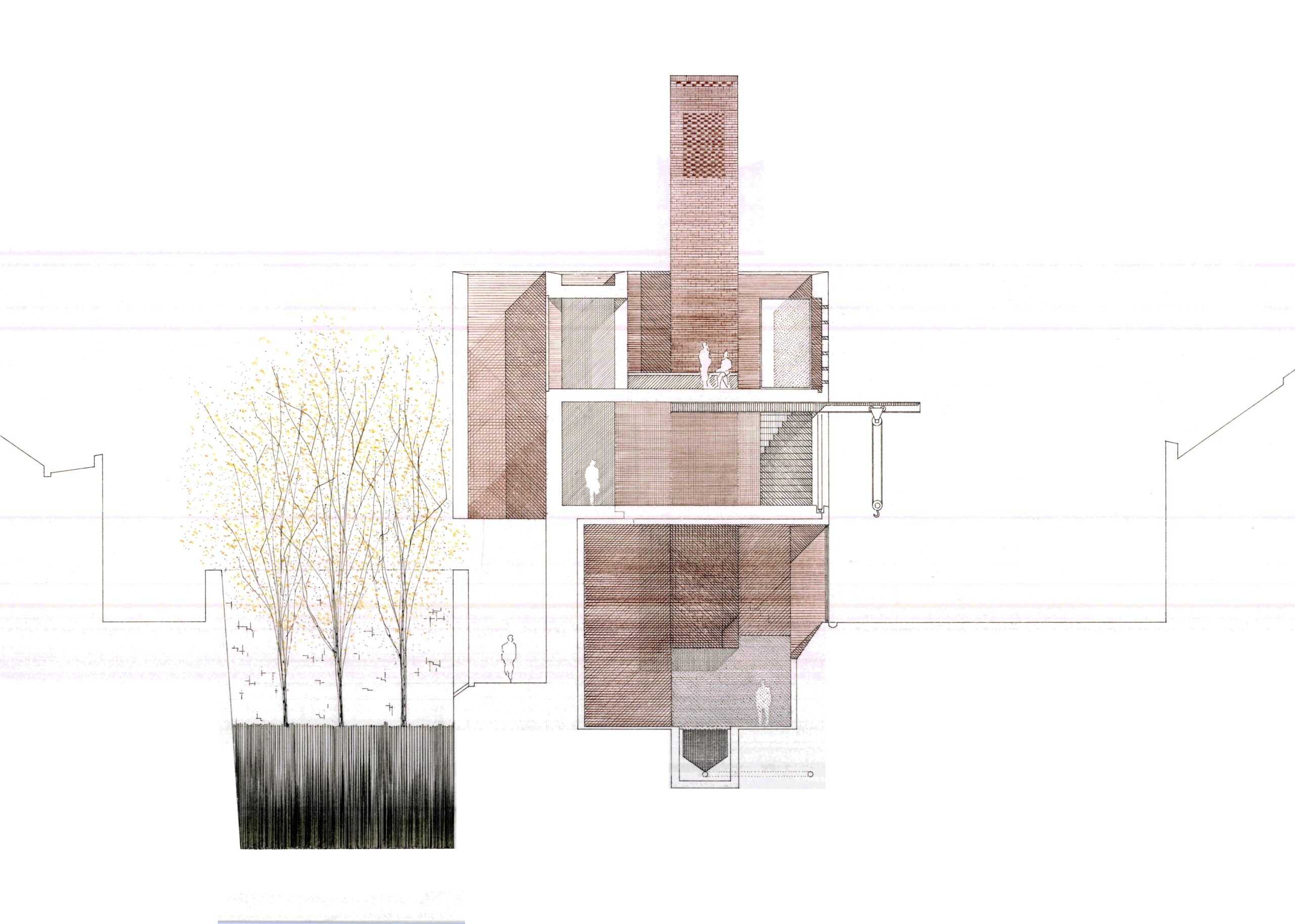

Heterotopia means ‘other place’. It is a term used to describe liminal social spaces in society where something different can occur. This thesis intends to explore the creation of nonprofit spaces that circumvent market-driven construction by imaging new uses for three vacant buildings on three laneways- Rutland Place, Grenville Lane, and Charles Lane- in the Mountjoy Square area of Dublin One. The typology of inner-city laneways has been chosen as a testing vehicle due to its high concentrations of dereliction and disuse that poses opportunity for the public reclamation of abandoned city space. In the context of our current housing shortages, a derelict house on the corner of Grenville Lane was chosen to further test a methodology of DIY housing that synthesises primary research about autonomous living from interviews with past and present squatters, and modular construction techniques derived from the self-build principles of Walter Segal and Enzo Mari. This open-source architecture makes use of standardised sizes and easily attainable materials to promote agile transport, quick (dis)assembly, and repeatability. A network of individual and connected ‘pods’ inhabit the building; communal working and living spaces are kept on the ground floor and thermally bound bedrooms on the upper. The structural system is designed as dually symbiotic and parasitic, bracing and stabilising the existing walls while breaking and swinging through openings in simple, yet playful ways. Underground public infrastructures like water and waste access are tapped into through surreptitious means, while electricity is produced using photovoltaic panels hooked up to a 12v battery. The DIY design process is intended as a blueprint of radical action; it interprets architecture as a tool of empowerment rather than imposition and posits that the possibility of changing the city relies not only on the structures of capital and state, but on the hands of its people.

Heterotopia Unbounded; Squatting the Laneways